|

|

|

|

|

Frederick I. Ordway III

© Frederick I. Ordway, 1979

Our address: en@rvsn.info |

|

See also: |

|

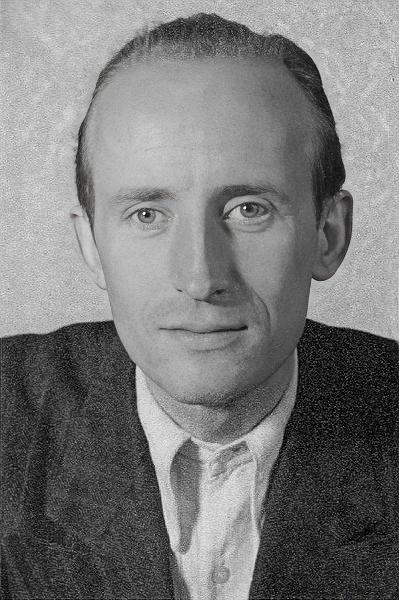

Gröttrup had graduated «with distinction» from the Technische Hochschule in Berlin in 1939 with a degree in physics. He had paid his own way through the university and even sent money home to his parents by serving as a technical consultant to various companies in Berlin. Following his graduation, he had spent six months in the laboratory of the renowned physicist Professor Manfred von Ardenne, an electron microscopist, before accepting a position at Peenemünde.

Gröttrup‘s reasons for going with the Russians were complex and varied. For one thing, he was unhappy with the contract offered by Colonel Holger N. Toftoy. His wife, Irmgard, later wrote in her book, Rocket Wife:

When hard facts are involved, civilization is thrown to the winds—first come, first served is the rule. The Americans were acting on that principle when, after ceding Thuringia—and with it Peenemünde, which bad been evacuated in the path of the advancing Russians—they grabbed Wernher von Braun, Hüter, Schilling, Steinhoff, Gröttrup and other leading rocket experts. We were housed at Witzenhausen and interrogated. After weeks had passed, Helmut was handed a contract offering him a transfer to the USA without his family, a contract terminable by one signatory only: the US Army. Since we wanted to remain in Germany, we moved back to the Russian Zone...

One should not infer that Gröttrup chose the Soviets because of political inclinations. Upon being interrogated by British and American intelligence personnel in 1954, Gröttrup struck his interviewers as being cooperative and having no discernible influences of Marxist philosophy. Later still, with two decades of reflection, his former colleagues at Peenemünde, then in America, drew an ambiguous portrait from memory: «an intelligent person, with a slight intellectual flair... Gröttrup’s ‘defection’ puzzled many people; probably, he saw too many competitors in the von Braun group... he was a liberal intellectual... he was a Communist... indispensable to the electrical side....»

In all events, it is unlikely that a Communist could have managed to rise to the position Gröttrup occupied in such a secret organization us Peenemünde. As incomplete a portrait as it is, perhaps the best of Gröttrup is that of Albert E. Parry, in his book Russia's Rockets and Missiles: «Complex personal grievances and ambitions rather than political convictions played their role here.»

As early as May 16, 1945, Gröttrup had told Major Staver in Bleicherode that he did not want to go to America. He also got into a violent political argument with Lieutenant Hochmuth at the same time. Nevertheless, he and his family were evacuated to Witzenhausen along with the other personnel of Mittelwerk. Once there, he again stated his position and turned down the US contract. Having refused the American offer, Gröttrup set himself up in the village as a dealer in scrap metal; such a mundane occupation simply was not for him, however.

At this time, he was approached by the Burgomeister of Bleicherode, who crossed the river Werra into the US zone to bring him an offer from a Major Chertok, a member of the Soviet Special Technical Commission and current officer in charge of reconstituting the plant at Mittelwerk. Gröttrup made two clandestine trips back into the Soviet zone to negotiate with the Soviets. Finally, in mid-September, he took his wife and two young children and returned to Bleicherode for good—or so he thought at the time.

Until he actually left for the last time, he tried unsuccessfully to do some local recruiting. In the nearby village of Ermschwerd, he attempted to will over Dr. Ernst Geissler. He explained to Geissler that the Russians were not the «bad guys» they had been painted and that he would he remaining in Germany while continuing his career. Geissler was not persuaded.

Once back in Bleicherode, where the Soviets furnished him with a fine home by simply moving its affluent merchant owner out, Gröttrup found out that the Russians intended to live up to their promises. His salary was set at 5,000 marks ($1,250) per month, although there was little he could buy with it in the Eastern Zone. Food was excellent; he and his family received the best rations available to the Soviet armed forces, even though most of it came from the local economy. His German employees were similarly well looked after: A typist made 300 marks ($75), and a working-level engineer earned upwards of 1,400 marks ($350).

Following their occupation of the Nordhausen area on July 5, the Soviets immediately set about putting things into order. There was some debate over whether the equipment and materiel in the region ought not be collected and shipped to the USSR. However, men such as Colonel Grigori A. Tokady, chief rocket scientist for the Soviet Air Force, later recalled the circumstances in his book Stalin Means War (1951):

The problem we face today is this: we have no leading V-2 experts in our zone; we have no complete projects or materials of the V-2; we have captured no fully operational V-2s which could be launched right away. But we have lots of bits and pieces of information and projects which may be very useful to us. We have the free or compelled co-operation of hundreds of German workers, technicians, and second-rate scientists, whose experience could be of value to us. In the circumstances, I think the best thing to do is to organize all these into a group, in Peenemünde, to give it a set task, and to find out what it can do for us here in Germany.

The logic o f this view prevailed, for a while at least.

The Soviets set two immediate goals at Niedersachswerfen: reconstruction of a full set of production drawings for the V-2 and reestablishment of a pilot production line for the missile. To accomplish these aims, the Institut Rabe— Raketenbau und Entwicklung (rocket manufacture and development)—was formed. It was under the command of the Soviet Special Commission (Nordhausen), in Berlin, under a General Kuznetsov initially and later a General Gaidukov. A group of Germans was also at work in the old Mittelwerk, largely engaged in writing manufacturing procedures and putting its facilities in order. The test stands at Lehesten were in perfect shape, since they had been left untouched by the Americans for the Soviets. The Gema plant in Berlin, an organization primarily concerned with missile control systems and the development of antiaircraft rockets, was also made a part of Institut Rabe.

In early 1946, four additional elements were added: Zentralwerke, Nordhausen, Werk II; Sommerda; and Sonderhausen. Zentralwerke consisted of a pilot production line in the old V-2 repair depot at Klein Bodungen. Nordhausen, Werk II, also known as Montania, assembled V-2 engines and propulsion equipment. In Sommerda, some 80 miles east of Leipzig (in the former Rheinmetall Borsig plant), a large design office and laboratory was set up. A factory for manufacturing all electrical equipment for the V-2 was set up in Sonderhausen, 12 miles south of Nordhausen.

In addition to reconstructing the V-2 and its manufacturing line, Gröttrup had the additional duty of developing two special trains given the deliberately misleading nomenclature of Fahrbarbare Meteorologische Station FMS (Mobile Meteorological Station). Each had between eighty and one hundred cars and provided full facilities, men, and materiel needed to prepare and launch V-2s. T here were sleeping and dining cars, laboratory cars, as well as freight cars for the V-2s and their launchers.

Gröttrup, in the spring of 1946, was placed in charge of Zentralwerke and was asked by General Gaidukov to take over responsibility for all guided missile development being done in the Soviet zone by Germans. In less than a year, his organization grew from the thirty-man Büro Grö (his initial office) to the five-thousand-man Zentralwerke. Between September 1945 and September 1946, he accomplished all that the Soviets had asked of him. The drawings had been redone and a pilot production line was turning out flightworthy V-2s. By the beginning of September 1946, some thirty rockets were ready. When parts could not be obtained in the Soviet zone, representatives of Zentralwerke contracted for them in the British and American zones. More often than not, they were bartered for food, drink, and tobacco rather than paid for with money. The completed components were smuggled into the Soviet zone by bands of «adventurers» paid in a similar fashion.

In lieu of launching, the V-2s from Zentralwerke were static-fired at Lehesten, where a stand that would take the complete missile had been constructed. This facility, under the direction of Valentin P. Glushko, fired its first V-2 propulsion system on September 6, 1945. Firings were conducted at first by Dr. Joachim Umpfenbach. Later, Soviet crews under Glushko performed tests as they became qualified through the tutelage of the Germans.

In the summer of 1946 the Russians asked Gröttrup's team to suggest technical improvements in the V-2 by mid-September. Some 150 such proposals were made, most of them based on concepts that had originated at Peenemünde. The Soviets accepted about half of them and asked that the other half be studied in greater detail before being resubmitted. Among the improvements the Russians accepted were pressurized propellant tanks; the relocation of all control equipment behind the propellant tanks; and turbopumps for the propellant driven by exhaust gases tapped off the V-2 engine.

Also, by mid-1946, Sergei P. Korolev, General Gaidukov's deputy on the Soviet Special Commission, was busy with calculations on an improved V-2, known to British intelligence as K 1. Korolev himself was more interested in the airframe and propulsion systems than the guidance and control systems, with which he had little experience. The new missile was essentially a «stretched» V-2. By lengthening the propellant tanks of the German missile by some 9 feel and increasing the thrust of its engine from 25 tons to 32 tons, Korolev produced a design that had an estimated range of 400 miles, or about twice that of the V-2. His one difficulty lay in the fact that the V-2 turbo pump was not designed for the higher flow rates he required. He chose to remedy t he problem by adding a second pump in series and ignoring German advice for the «bootstrap» of exhaust gases from the engine back into the turbopump. He did like their idea of a warhead compartment separated by explosive bolts from the rocket body, when its engine had shut off, to increase its speed.

Indeed, Korolev, who spoke and understood German, made as little use as he could of the Germans in Zentralwerke. Thus, at that early date, it became apparent the Russians were clearly on the road to independence in missile development.

The production drawings for the K 1 were all in Russian and were sent to the manufacturing facility at Sommerda from the Special Commission headquarters in Berlin. The drawings, which were different from those used to manufacture the V-2, apparently had been made in the USSR. All components for the K 1, including standard V-2 components made in other facilities of Zentralwerke, were crated and sent to the USSR. Some of them went to Zavod 88 (Factory 88), a rocket plant formerly producing oil-well drilling equipment until the machinery was evacuated to the Urals in 1942. Zavod 88 was located in Podlipki (later renamed Kalinin grad), some 10 miles northeast of Moscow. Other components were shipped to Zavod 456 in Khimki, 4 miles northwest of Moscow, a plant where jet engines for aircraft and rocket engines for missiles were being built. None of the K 1 missiles were destined to be launched or test-fired in Germany.

In the autumn of 1946, Gröttrup was asked to produce a rough design for a missile with a range of 1,500 miles, with no specification as to warhead weight or accuracy. Such a sketch was completed in a few days and handed over to Korolev for transmittal to Berlin and thence to Moskow. Gröttrup had based it on the A 9/A 10 concept developed a few years earlier at Peenemünde.

Relationships between the Germans and the Russians were proper and in some cases even friendly. There was a brief period of initial distrust on the part of both, however. The Russians were suspicious o f the true intentions of the Germans to put forth their best effort in reconstructing the V-2 or making improvements on it. Some even feared that the Germans would actively sabotage such efforts. The Germans, on the other hand, worried about the permanence of their jobs and had the nagging fear of being sent to the USSR.

Gröttrup in particular got along well with Korolev, being very impressed by Korolev's professionalism and the respect shown him by the other Soviet engineers. Korolev had a sympathetic ear for the personal problems of the Germans at Institut Rabe, and on one occasion used his authority and energy to rebuff an MVD (secret service) attempt to harass Gröttrup’s secretary.

— — —

Things were going well for the Germans in Bleicherode and the vicinity as autumn of 1946 approached. A meeting had been scheduled for early October to discuss improvements to the V-2, but was postponed until October 21. The conference was a spirited one and presided over by General Gaidukov. Proposed plans for increasing the range and accuracy of the rocket were discussed, and Gaidukov seemed to be in agreement and at his amiable best. Following the meeting, he insisted that Gröttrup and his managers join him in a party. Gröttrup knew that he could forgo any plans for getting home at an early hour. He had been a guest at Gaidukov’s parties on the latter’s previous visits to Bleicherode.

The party began with the inevitable toasts to comradeship between the Russians and the Germans, and they were made with the best vodka, shipped in seemingly endless quantities from Moscow. The Soviet toasts were returned by the Germans as protocol demanded. These, in turn, prompted another counter round of toasts by the Russians. Thus the party continued until 4:00 am on October 22.

An hour or so before the party broke up, Irmgard Gröttrup was awakened by a telephone call from the wife of one of her husband’s engineers. The distraught woman asked if Irmgard was going to Moscow with the other Germans of Zentralwerke!

«For Heaven's sake! What a time for bad jokes! You must be drunk,» she said as she hung up the telephone.

It was the first of a series of calls that continued for an hour or so. Later, Irmgard recalled:

Then there was the sound of powerful engines... Cars stopping at the door. How many? Beginning to realize what was happening, I jumped out of bed. From every window I could see Russians; the house was surrounded by soldiers with tommy-guns. Outside were cars and lorries, nose to tail.

Someone pressed the front door bell and kept his finger on it— fists hammered on the door—the noise echoed through the house.

The same scene was being played all over the Soviet zone. A t each of the homes of the some six thousand German citizens employed by the USSR, a young army officer pounded upon the door and upon its opening immediately began reading:

As the works in which you are employed are being transferred to the USSR, you and your entire family will have to be ready to leave for the USSR. You and your family will entrain in passenger coaches. The freight car is available for your household chattels. Soldiers will assist you in the loading. You will receive a new contract after your arrival in the USSR. Conditions under the contract will be the same as apply to skilled workers in the USSR. For the time being, your contract will be to work in the Soviet Union for five years. You will be provided with food and clothing for the journey which you must expect to last three or four weeks.

The notice was the culmination of a plan, the last details of which had been worked out several days previously by Colonel General Ivan A. Serov, deputy special commissioner of the Soviet Military Administration in Germany and first deputy of the MVD. His operation between October 12 and 16 resulted in the removal of some twenty thousand Germans to the Soviet Union. They were transported there in ninety-two trains that had been previously positioned at railway stations throughout the Soviet zone of Germany.

Irmgard, once the initial shock had worn off, called Gröttrup. His voice held nothing of reassurance: «Do be sensible! General Gaidukov is with me, the room is full of officers—You understand, don't you? There is nothing I can do. I may come home, on the other hand I may not see you until we get on the train. I may have to fly over in advance or follow afterwards.»

As events transpired, the Gröttrups were to travel to the USSR in three compartments of the sleeping cars parked on the siding at Klein Bodungen. However, it was 3:00 PM on the following day before the train departed. Several members of the group had yet to be rounded up. A Dr. Ronger appeared with a nearly incredible story: The Russians had orders to evacuate him and his wife. Ronger's wife had died three days previously, and the Russians urged him seriously to take any woman he wanted—he could get married in Moscow.

The train had scarcely got under way before Gröttrup was dictating to his secretary. Entitled «Official and Formal Protest Against the Deportation of Central Works Employees to Russia,» the lengthy document opened with the preamble: «In the numerous discussions which went on right up to the aforementioned dated of 23.10.46, the delegates of the Special Commission, and in particular Colonel Korolev and General Gaidukov, repeatedly stressed that a removal of the works to the USSR or any part thereof would only he considered within the next few years.» When the protocol was presented to the Russians, who suddenly seemed much more distant and far less friendly than they had at Zentralwerke, the result was predictable. Nyet!

The train arrived in Moscow on October 28, as Irmgard recorded in her diary:

We were neither gassed nor received at the Kremlin. It all happened like this: General Professor Kolsianovich [in fact, Pobedonostsev] was waiting with a few officers to welcome us on the platform. I had known him and some of his officers in Germany so it was quite a pleasant reunion. He advanced towards me with outstretched hands as if I were his personal guest: «Welcome to Moscow! What have you brought for me? A cheerful mood, I hope!»

On the arrival in the USSR, the Germans from Zentralwerke were split into two approximately equal groups. One was sent on to the island of Gorodomlya in Lake Seliger, some 150 miles northwest of Moscow. Conditions on the island were incredibly primitive, and the island was in a region that had seen some of the bitterest fighting on the Russian front only four years earlier, in January 1942. As a result, the Nemets (Germans) were received with outright hostility by the local Russians. The other group, the Gröttrups among them, was settled in the northeastern section of Moscow, near Datschen, in relative comfort.

The Gröttrups rated a six-room villa with an entrance hall and two anterooms, the home of a former council minister. The other members of his staff did not fare so well. They were quartered in great mansions of tsarist days: one room to a family of three, two rooms to a family of four, with university graduates having an additional room.

On November 4, the Gröttrups’ BMW automobile arrived from Bleicherode, but they could not drive it since they had no Soviet driver’s licenses and the Russians did not recognize international permits. However, their obliging hosts provided them with a chauffeur, Ivan Ivanovich, who soon proved to be a great help to Irmgard, protecting her from rapacious and conniving Moscow pickpockets.

The Germans worried about when if ever they would be permitted to return to Germany. The salary situation also was a critical issue, odd as this may seem under the circumstances. The Germans arrived in Moscow with no contracts, and the Soviets seemed in no hurry to draw them up. Negotiations proved useless. After attempting to reason with the Russians for several months, Gröttrup simply went on strike on April 30, 1947. He refused to go to his office in Nauchnii isledovtaelskii institut Nii-88 (Scientific Research Institute 88). He presented a list of ten or so complaints to General Leo Gonor, the commander, who ignored them completely. However, on May 2 salaries were set. In general, they were much lower than the previous monthly stipend. Gröttrup’s wages were set at 8,500 rubles monthly (he had been receiving 10,000). Even so, this sum was four times that paid to his Soviet counterpart in industry.

Relatively few rocket specialists such as Gröttrup were transported to the USSR—only two hundred men and their families were taken from among the live thousand employed by the Zentralwerke. The remainder were individuals currently working in production and research facilities in every field of technology and science. In each case, their fate was the same. It is described by Robert A. Kilmarx in his book A History of Soviet Air Power:

The pattern of exploitation ran along these lines. A German design team in Russia would be given specifications on which to base an independent developmental project. In most cases original German ideas were eagerly sought. Russian engineers and technicians were attached to the German groups and learned all they could from them before being replaced by another group of trainees. At a certain stage, an independent Russian design-research team would be established. The team would siphon off German advances and incorporate them into its own work. From time to time progress among the Germans would he investigated by the Russians and the project might even be canceled—if the state of Russian progress or priorities so dictated. By the early 1950s, the usefulness of most groups of Germans had passed and, after a cooling-off period, they were allowed to return to Germany. Only in certain critical areas like missile guidance were the captured [sic] Germans retained longer.

The first six months in Moscow continued to be chaotic. While most of Gröttrup’s men stayed with him or went to Gorodomlya Island, several key members of the former Zentralwerke were sent to the Communications Ministry, the Air Ministry, and other organizations. Furthermore, engineers and scientists from other institutions or companies evacuated at the same lime as the Zentralwerke were gratuitously assigned to Gröttrup. In none of the personnel changes was he consulted. It was clear that the Soviets had no idea of using the Germans as a team, in Moscow at least. Those on Gorodomlya Island, however, were so organized and utilized.

Conditions at Nii-88 were later described by Irmgard:

Here the men have to make do with badly equipped laboratories and take to work such tools and apparatus as they still happen to have among their private possessions.... What’s more one of the men even look the kitchen alarm clock to pieces because the clockwork had the very steel spring he needed so urgently! To his wife's exclamation: «Surely this joke is going too far? Aren't there any steel springs in this strength to be had in the whole of Russia?» He replied: «Not in stock, and it would take a year for the head of the buying department to get them.»

— — —

One of the first tasks for the people a t Nii-88 was to assist the Soviets in setting up a pilot production line for the V-2 in Zavod 88. The guidance and control experts on Gorodomlya went to work on building a Bahnmodell, a simulator for rocket trajectories, which was completed in about a month and sent to Nii-88. Work in both locations was hampered by the fact that the documentation from Zentralwerke had not accompanied the personnel in October. Indeed, it did not arrive until the summer of the following year. Thus, on many projects, engineers had first to reconstruct the drawings and documents that were lost somewhere in the Soviet bureaucracy. A team of some twenty Germans under a Dr. Putze had been sent to Zavod 456 to work with its new director, Valentin P. Glushko. However, Glushko did not like the Germans and largely ignored them; he made no effort to stop Gröttrup’s request to have them transferred to Nii-88. Still other propulsion specialists, such as Dr. Ferdinand Brandner, wound up in Kuibyshev under the direction of A. G. Kostikov, who had developed the solid-propellant Katyusha rocket of World War II.

During Gröttrup's strike, Professor Colonel Yuri Pobedonostsev, chief engineer at Nii-88 to whom he reported, gave Gröttrup a report to read «during the holidays,» as the Russian put it. It was «Über Einen Raketenantriebe Fernbomber,» dated August 1944, and prepared by Dr. Eugen Sänger and Dr. Irene Bredt of the Deutsche Luftfahrtforschung in Ainbring, only a hundred copies of which had been printed. In it, Sänger and Bredt proposed an «antipodal» bomber—one that would be boosted into space by a large rocket, circle the world by alternately dipping into the upper atmosphere and pulling up until it reached the target, drop its bomb, and by the same maneuver return to its base.

The Soviets were at the time showing great interest in the report, On April 14, there was a meeting at the Kremlin in the office of M. A. Voznesensky, deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers, chairman of the State Planning Commission, and member of the Politburo. Present were G. M. Malenkov (who would later succeed Stalin), deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers, and second secretary of the Central Committee; D. F. Ustinov, minister of armaments; Air Marshal K. A. Vershinin; A. S. Yakolev, aircraft designer; A. I. Mikoyan, aircraft designer; Lieutenant General T. F. Kutzevalov, Soviet Air Forces; Colonel G. A. Tokady, chief rocket scientist of the Soviet Air Force; and M. V. Khrunichev, minister of aircraft production.

They were there to discuss the technical feasibility of the Sänger project and were looking to Tokady for an expert opinion. The colonel (as described in his book Stalin Means War and articles in Spaceflight magazine) explained that he had been given only the briefest time to examine the very detailed and highly technical report. Nevertheless, the group pressed him for an answer, especially Voznesensky. After some hesitation, Tokady replied that he «was inclined to think that Sänger was a gifted scientist but rather academic and lacking in practical experience.» He also thought that Sänger's «physics and mathematics should be carefully checked.» A day later found Tokady in the presence of Josef Stalin and the Politburo Council of Ministers. Stalin’s mind was probably made up before he listened to the colonel's opinions of the Sänger proposal. Still the latter expressed his opinions rather freely. He mentioned that the Germans, for example, were at least ten years ahead of the Russians in jet- and rocket-propelled aircraft and missiles. Stalin, then, replied, «In other words, we shall have to learn from the Nazis—is that it?» Tokady was hesitant to answer the question; when he was pressed by Stalin, he said, «It is hard for me to say, Comrade Stalin; perhaps the Germans have given more thought to war than we have. Perhaps in their history militarism occupied a more fundamental place.»

Stalin permitted the colonel to speak for some three-quarters of an hour. Later, Tokady recalled:

Sänger had produced a number of stimulating notions, but he was not an engineer. I suspected some of his equations: my own calculations so far suggested that he was wrong in putting the thrust of his machine at 100 tons. In any case, we had no experience in the field of rockets, we lacked the men, the research institutes.... Our metallurgists had not yet produced metals sufficiently heat-resisting to use for the combustion chamber....

At the time, Tokady’s choice o f words worked to his disadvantage. To those in the room, he seemed to be implying that the USSR thought of war and espoused militarism, both of which were counter to the current «party line.» He was reprimanded for his words after the meeting by Serov.

The result of the conference with Stalin was the formation of Special Commission No. 2 for investigating the Sänger project and reporting directly to the Council of Ministers. (Curiously enough, it had not only a title similar to that of the special commission headed by Hans Kammler in the latter days of the war in Germany but also had a similar purpose.) It was directed by Serov, with Tokady as the deputy. Also on the committee was Major General Vasily I. Stalin, the son of the premier. The commission went off immediately to Berlin to pursue its task of coming up with a final report by August 1, 1947. However, like so many bureaucratic undertakings in the USSR at the time, the commission failed to provide any useful information, and the project came to naught.

Later in 1947, the Sänger report was sent to the Germans on Gorodomlya for further study and comment. Apparently, someone in Moscow still held hopes for the concept. However, they received little encouragement from the Germans, who doubted the calculations of a mass ratio of 0.1 postulated by Sänger. (The mass ratio of a rocket vehicle is the empty weight divided by the weight at launch. The value proposed was about that realized some two decades later with the American Saturn 5 rocket.) Additionally, they pointed out that the «skip» flight path foreseen for the winged craft would impose severe loads on the wing root structure and that Sänger did not say how they were to be accommodated. Gröttrup himself did not believe that an exhaust velocity of 9,900 to 16,500 feet per second and a chamber pressure in the engine of 1,470 pounds per square inch was attainable with the current Soviet technology. He also felt that Sänger had inadequately dealt with the problems of reentry. The method of launching, from a 1.8-mile-long ramp, also seemed to have no advantage over a vertical lift-off. All in all, the Germans corroborated the criticism of Tokady, and there probably was no subsequent attempt to build the «antipodal bomber,» once the Soviets appreciated the advances in the state of technology it required and their own shortcomings in fields such as high-temperature metals.

— — —

The Germans also were asked to design a new rocket, the R10. Actually, they had started limited work on the project while still in Germany, and the rocket was then labeled G1. By early autumn 1947, the documentation and drawings for the R10 had reached an advanced stage, even though the Germans did not have access to their previous drawings done at Zentralwerke. Both the Germans at Nii-88 and at Gorodomlya were occupied on the project.

R10 was one of the few projects on which Gröttrup’s men would work together or, in modern industrial terminology, «apply the systems engineering approach.» The rocket design that emerged had features that would also appear in the first generation American missiles designed by Wernher von Braun's team in the United States.

R10 was to be 46.5 feet in length and 5.3 feet in diameter, practically the same dimensions as the V-2. It would have a gross weight at launching of 40,590 pounds, compared to the 28,170 pounds of the V-2. The empty weight would be 4,235 pounds, versus the V-2's 8,810 pounds. Thus, the R10 mass ratio would be about 0.1, while the mass ratio of the V-2 was 0.31. The difference lay in the fact that the R10 would have a separable warhead, whereas the V-2 warhead remained attached to the 2,000-pound empty rocket body.

The R10 would feature a modified V-2 propulsion system, producing 70,400 pounds of thrust using liquid oxygen and ethyl alcohol. The V-2 produced only 55,000 pounds. The additional thrust was to be obtained by increasing the flow rates of the propellants to the engine, which raised the combustion chamber pressure to 294 pounds per square inch, compared to the 227 pounds per square inch of the V-2. The interior surfaces of the chamber were to be cooled, as was that of the V-2, by emitting a film of alcohol through small holes in its wall.

While the R10 would bear an external and superficial resemblance to the V-2, its structure was innovative. Gone were the internal aircraft-type propellant tanks surrounded by an aerodynamic shell. The R10 would have featured a monocoque structure, in which the pressurized propellant tanks formed an integral, load-bearing part of the rocket. (This weight-saving technique was also utilized in the Atlas, America’s first intercontinental ballistic missile, and Britain’s short-lived counterpart, the Blue Streak.) To lighten weight, and hence increase range, the propellant tanks were to be of very thin aluminum or steel.

These tanks were pressurized to two atmospheres. The liquid-oxygen tank was pressurized by the natural «boil off» of the liquid oxygen. The fuel tank was pressurized by the cooled gas tapped from the turbopump.

The high-test peroxide generator of the V-2, used to provide steam to turn the turbopumps, was done away with in favor of utilizing gases from the combustion chamber piped back to them. Initially, the pumps were brought up to speed on the launching pad by means of compressed nitrogen from a source on the ground. A weight savings of some 400 pounds was thus achieved.

The control section for the missile was moved to the aft end from its forward position in the V-2.

At the point in the trajectory where the propellants were cut off, the warhead was separated from the rocket body with no loss in momentum by two small retro-rockets on the body, fired at the moment the engine shut off, and they, in effect, backed the body away from the warhead. The warhead was covered with plywood, which in charring upon reentry into the atmosphere protected the explosive from the heat so generated. A steel warhead case was also designed at the request of the Soviets.

The R10 was to be controlled by means of jet vanes, as was the V-2. However, while there were small fins on the aft of the missile, they had no movable aerodynamic surfaces as did those of the German rocket. An improved servo system for the vanes obviated the need for these surfaces on the fins.

Guidance for the R10 consisted of «beam riding,» in which four antennas on the ground established the very narrow beam path in vertical and horizontal planes. The missile lifted off vertically and was programmed to pitch over into the guide beam. Velocity was measured by an on-board Doppler transponder. Once the proper velocity for a given range was reached, the engine shutoff signal was sent to the missile. The range of the missile was considered to be about 570 miles and its accuracy would theoretically have 25 percent of all missiles fired falling into a square 0.6 mile on a side.

Despite this quantum leap in rocket technology, there is no indication that the Soviets went into serial production with the R10. However, they did adopt many of its features, especially the guidance scheme, for the wholly Sowiet-designed missiles that appeared in the early 1950s.

— — —

In the autumn of 1947, Gröttrup took a break from his duties at Nii-88. It was not, however, a holiday.

On August 26, he was ordered onto the FMS-1 train along with several other Germans, such as Dr. Kurt Magnus, the gyroscope expert; Dr. Johannes Hoch, chief of Guidance and Control at Gorodomlya; Karl Munnich, an electronics and radar expert from the Ministry of Communications; and two propulsion test engineers from Zavod 456, Alfred Klippel and Otto Meier. He left in such haste he was not permitted to telephone his wife. The train wound southward for almost a week before turning eastward into the steppes beyond Stalingrad (now Volgograd). It halted in a siding of the Ryazano-Uralskaya Railway in the village of Kapustin Yar, some 75 miles from Stalingrad. The FM S-2 train was already there, apparently with a full military complement aboard.

Gröttrup and his colleagues were at the railhead of the Soviet Union's first long-range rocket range, upon which construction had begun earlier in the summer. It was still a primitive place, though. It had been built by some eight thousand military engineers who were still at the site living in American army tents. They were there to assist in launching the first V-2s.

Among the Soviet dignitaries on hand was Colonel Spiridonov, the affable commander of Branch No. 1 of Nii-88, as the Germans on Gorodomlya were denominated; he spent most of his time in the club car of the FMS-1 train, living up to his sobriquet of «Rumbarrel» bestowed on him by the Germans. Marshal Nikolai N. Voronov, commander of the artillery that effected break-through of the Mannerheim Line in Finland in 1939 and also artillery commander at Stalingrad during World War II, was there. With him was Col. Tyulin, a leading ballistician from the Academy of Artillery Science, the commander of which in 1950 would be Voronov. Also from Nii-88 were Kurilo, head of the assembly shop, and Ginsburg, an electrical engineer, both of whom were constantly busy readying the V-2s.

Next to the railhead was an equipment dump, largely in the open. Gröttrup recognized some machinery from Zentralwerke and Lehesten rusting away. Some 2 miles to the north was a din airfield. And about 9 miles to the northeast lay the range head proper. It consisted of a horizontal test stand for checkout of the V-2s and a rail siding for the shop cars of the FMS-2 train. A mile or so to the east was a vertical static-firing test stand on the cliff of a dried river bed also with a rail siding for other cars of the FMS-2. About a mile and a half to the northwest of the static firing stand was the launching point itself. It was served by FMS Car No. 28, which had the same function as the Fürleitpanzer did in the mobile V-2 battery. Nearby were the German Messina and Hawaii telemetry receiving antennas. (The Soviets also attempted to measure the attenuation of radar signals passing through the highly ionized exhaust stream of a rocket motor. Curiously enough, the experiment was made with an American SCR-548 radar, which had tracked British-launched V-2s in Operation Backfire.)

As Gröttrup worked at Kapustin Yar, living in one of the sleeping cars of FMS-1, Irmgard had no word from him and could find none at Nii-88. Her continual harassment of the officials, however, paid off.

On October 19, she was permitted to fly to Kapustin Yar to be with him. She was destined to be one of the few females at the range. (Another, in an official capacity, was Mme. Katya Chernikova, chief of the laboratory at Gorodomlya that was concerned with electrical measurement instrumentation.) Irmgard's diary later offered a revealing glimpse of living conditions on the steppes:

The testing ground is some way off: a launching base and testing ground for carrying out tests on the automatic and electric controls of the unfuelled rocket, and a test-bed for the firing of fully loaded rockets.... We also have a mobile army bath unit. The instructions for us are to enter the carriage, knock on the wall and wait until the Moujik [peasant] has pumped water into the water container. Then turn on shower. I go in and knock and proceed to soap myself well all over. I turn on the shower but nothing happens. The Moujik has fallen asleep.

While Irmgard Gröttrup contented herself walking in nearby Kapustin Yar, where there were more camels than cars, and enjoying the incredibly sweet melons grown on the collective farm nearby, her husband was extremely busy. Kapustin Yar was no Peenemünde by any means, although practically all of the equipment there had come either from Peenemünde or Lehesten. There were green US army tents instead of the sturdy masonry barracks that had housed the soldiers of the VKN at Peenemünde. Gröttrup lived and worked in a train rather than the modern BSM Haus as he had done at the center on the Baltic.

On October 27, as the last details were being taken care of for the launch of the first V-2 only two days away, Gröttrup was talking with a group of visitors from Nii-88 when suddenly a Russian worker fell 65 feet from a scaffolding and cracked his skull. Gröttrup turned pale, but his Russian visitors did not miss a word of conversation as the late worker was dragged away by his fellows. A day later, a beam came loose and crashed to the ground, killing a leader of a welding group sent in from a factory in Stalingrad to assist in getting the range ready. Again, there was no discernible reaction among the Russians. Clearly, industrial safety, which had been closely checked at Peenemünde, was of no concern at Kapustin Yar.

Irmgard was on hand for the launching of the first missile on October 30. She later recorded her impressions:

Last night, probably the most exciting and memorable of all nights in Russia, no one can have slept. Differences in rank simply ceased to exist; there were no more professors, ministers, or officers, just one enormous wildly excited family.... It was just like Peenemünde when we made our first experiments and I went to Helmut's room only to find that it was occupied by an exhausted professor from Dresden University... The queen bee of our hive is the rocket!

A beautiful clear morning dawns over the steppes of Kazakhstan.... The tension has become so acute that I could scream.... We are off! «Zero minus 10... zero minus 9... zero minus 8... zero minus 7... zero minus 6... zero minus 5...» Suddenly the launching platform collapses sideways and with it the fully loaded rocket. One leg of the platform has given way....

We make a dash for the bunker, while workmen run toward the rocket and, with absolutely no sign o f fear, winch the whole thing back into position, platform, rocket and all, and prop it up with girders. There's Russia for you!

The countdown was resumed, and the rocket was launched. Then there followed a few emotionally charged minutes as everyone wailed for the word from the Askania cinetheodolite stations, the superb monitoring equipment which came from Peenemünde, lining the route of the missile as it sped almost due east. Suddenly, Minister of Defense Armaments Ustinov grabbed Korolev in a bear hug and danced him about. Korolev, in turn, did the same with Gröttrup. There was almost pandemonium at the launch area as word was announced that the rocket had flown almost 175 miles and landed reasonably near the target.

Gröttrup, however, soon overcame his emotion. The fact that the first launch was so successful was simply a statistical occurrence that could easily have gone the other way, as, indeed, it had done at Peenemünde when the first V-2 was launched.

«We can't play around here like naked savages,» he said to his wife. «Besides, there is more to come tomorrow. The next missile has to be got ready!»

On the next day, the second V-2 behaved just as badly as had the first one at Peenemünde. It began rolling faster and faster about its longitudinal axis until the fins sheared off and the rocket tumbled into the ground from an altitude of about 500 feet. While Ustinov began muttering to himself about the possibility of sabotage, Gröttrup and his launching chief, Fritz Viebach, merely shrugged. Korolev sympathized with his German associates. Being the engineer that he was, he knew that the complexity of the V-2 made perfect take-offs each time an impossibility.

— — —

In all, some twenty V-2s were launched from Kapustin Yar before the Gröttrups were permitted to return to Moscow, which they did on December 1,1947, traveling on the FMS-1 train, that had been parked in a siding near Nii-88.

A variety of warheads or payloads was fired during this series. Some were merely instrumented ballasts to determine heats of reentry, etc. Others were the standard, high-explosive warhead used with the tactical V-2. Yet others were scientific instruments to measure the cosmic ray flux above the sensible atmosphere. These instruments were supplied by the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, several members of which were present for the firings.

The twenty-odd V-2s were launched alternately by Viebach's all-German crew and an all-Russian crew under the direction of L. A. Voskresensky, who at Zentralwerke had been Soviet manager for the development of the FMS trains. Upon removal to Nii-88, Voskresensky rose rapidly. He became a member of the Nauchnii Tekhnicheskii Soviet (Scientific and Technical Council) NTS of Nii-88 and an assistant to Korolev. (In later years, he would become Korolev’s deputy as a space vehicle systems designer and play a key role in the early manned space flight programs of the USSR. He died on December 15, 1965, only a month before Korolev.)

Scarcely had Gröttrup settled down to the routine at Nii-88 than he was called upon to attend a meeting of the NTS. This group was a policymaking body for Nii-88. Some eighteen or twenty members were associated with the establishment while others were not. Gonor, Korolev, Pobedonostsev were all members. Glushko from Zavod 456 at Khimri was a member, as was a Professor Frankel, an Austrian aerodynamicist who had emigrated to the USSR in the early 1930s. Academician Mikhail K. Tikhonravov was there, too. He had worked with Korolev and Glushko a decade earlier In Moscow as a member of the Group for Studying Reaction Propulsion, which built and static-fired liquid propellant rockets.

Meeting with the Russians across the red-draped tables on the ground- floor conference room of Nii-88, next door to the technical library, were most of the department heads from B ranch 1 of Nii-88. Among those present were Dr. Waldemar Wolff, chief of ballistics; Dr. Werner Albring, chief of aerodynamics; Dr. Joachim Umpfenbach, chief of propulsion; Engineer Josef Blass, chief of design; Dr. Johannes Hoch, chief of guidance and control; and Dr. Franz Mathes, chief of propellant chemistry.

The occasion was similar to an academic event in the West where a candidate for the PhD degree must defend his dissertation against his faculty. The Germans earlier had been asked to propose a design for the R10 rocket. Their first attempt had not pleased the Russians of the NTS, who demanded more details. The Germans now had returned with more than two hundred detailed drawings and several hundred pages of engineering reports, including the involved mathematics that so pleased the Russians. Impressed, the committee approved the project and allocated the funds necessary to undertake it provisionally.

However, the Germans were to be disappointed. For all their hard work, they were assigned very few tasks on the program. They were permitted to do some structural testing of the missile body and to assist in the development of the gas-bleeding process for driving the propellant turbopumps. They also worked some on the Doppler radio system for the R10 guidance and control. Other than these areas, they were not called upon. The Germans soon lost interest when it became apparent that they were not to be permitted to develop the overall rocket.

With the beginning of 1948, the Russians began removing Germans from Nii-88 and other locations in Moscow to Gorodomlya. Gröttrup was among them; he was not particularly downcast to leave Nii-88, but his pay was cut to 5,000 rubles. Umpfenbach took his place at Nii-88. Gröttrup's position and authority had gradually been eroded, both by the Russians and by several ambitious Germans who worked for him. On February 20, 1948, Gröttrup and his daughter Ulli left for the island, while his wife and their son Peter stayed behind for a few months because of the boy's illness.

To add to the low morale of the Germans at Nii-88, Korolev had decided to push ahead with his pet project, which was the improved V-2, begun at Zentralwerke and improved upon by features he had gleaned from the documentation produced by the Germans for the R10. He had the ear of General Gonor, and he had h is own fabrication shop adjacent to Nii-88, but he lacked the technical expertise of the Germans. These latter had no desire to work for Korolev on his project because it simply was no professional challenge. «Stretching» the V-2 to get another 75 or so miles range did not interest them. Also, if they went to work in his shop, their integrity as a team—or what was left of one—would be compromised. Thus, there was another motivation for not staying in Moscow.

«If we let Korolev have his own way, he’ll grab all the best people for himself and we shall be turned into mere drudges, or, at best, walking technical handbooks.... I proved to him ages ago that his plan of simply building a longer V-2 and providing it with a more powerful thrust won't materially increase the range,» said the perpetually gloomy Umpfenbach.

— — —

The lot of the Germans on Gorodomlya had improved considerably by the time the Gröttrups arrived. Earlier, in October 1946, when the initial group had stepped from the ferry that brought them across the lake to Oshtakov, they were met by the genial, bald, and rotund Colonel Spiridonov, an affable party hack and great friend of Ustinov, who was chief engineer on the island under its manager, Suchomlinov.

What the Germans found ashore were filthy and verminous huts, water that had to be hauled from the lake, and no sewage or public sanitation by Western standards. All of the «pioneers» assured the Gröttrups that things were immeasurably better than when they had arrived. Irmgard was hard to convince. Used to the luxury of a villa near Moscow and a chauffeur, she found it hard to adapt to her new quarters. Her diary furnishes evidence of her frustrations and privations:

15.11.1948. At nine o'clock I took a hatchet to the shed and hacked off a piece of frozen meat. By eleven o'clock when it was almost defrosted, I decided it was almost bones. So it had to be cabbage soup again. My stove, bearing the proud inscription «Made in Gorodomlya,» is incredibly primitive, constructed of clay and stones.... I'd much rather have windows that shut properly. I'd like some decent shoes for the children.... «What, cabbage again?» was the general outcry at lunch. Helmut was busy making calculations on the edge of the table. I pointed out to him that he was not setting a good example, but all I got in reply was an absent-minded glance and a remark about a fully automatic test stand....

During the remainder of 1948 and 1949, the Germans on Gorodomlya did some useful work. They were given selective design or consulting jobs on several rockets being considered by the Soviets. From the summer of 1948 until the spring of the following year, the group worked on the R12, a multistage rocket that would send a 2,200-pound warhead to distance of 1,500 miles. However, the engineering problems associated with stage separation and particularly second-stage ignition were so formidable that nothing came of this effort. In midsummer 1949, the Germans were consulted on the R13 rocket being studied at Nii-88. Curiously, it seemed to be a technical retrogression. It was to have a 2,200-pound warhead and a range of only 75 miles.

On April 4, 1949, Ustinov visited Gorodomlya with a proposal. He enlisted the assistance of the German group on the design characteristics of the R14, a rocket that would send a 6,600-pound warhead to a distance of 1,800 miles. He gave them three months to have preliminary designs ready but imposed no other limitations upon them.

The project in some ways breathed new life into Gröttrup’s people on Gorodomlya. The fact that a man as high up as Ustinov brought them the project seemed to indicate that it would be an important one, one in which they «would have a piece of the action.»

Several alternative approaches were considered. Some wanted to use as yet unproved high-energy propellants to boost performance. Others wanted to use multi-engines. Some thought that a two-stage or three-stage rocket would be required. Methodically, each one of these concepts was discussed and rejected or modified in some degree. The R14 finally proposed by the Germans was certainly no «updated» V-2. It was a new departure in rocket design. Indeed, at the time, it was considerably in advance of anything being proposed o r thought of by von Braun and his team in the United States. Branch 1 proposed a single-stage, conically shaped rocket 77.6 feet long and 9 feet in diameter. It had a relatively low initial acceleration, which meant that the structure of the rocket would not have to be excessively heavy. There were to be no fins or other aerodynamic control surfaces, and the rocket on the pad would weigh some 156,200 pounds. With an empty weight of about 15,400 pounds, including a 6,600-pound warhead, the Germans were proposing a vehicle with a mass ratio of 0.1. The monocoque structure was to be of pressurized stainless steel tanks for the propellants and the warhead section, although the plywood ablation technique for cooling the warhead was maintained.

This version of the R14 utilized alcohol and liquid oxygen. (The Germans seemed to have a technological fixation on this combination, both in the USSR and the US, simply because they were familiar with it.) The engine was to have a thrust of 220,000 pounds, with the combustion chamber regeneratively cooled by circulating alcohol through its walls. The turbopumps for the propellants were to be driven by hot gases «bootstrapped» from the combustion chamber of the main engine, as had been proposed with the R10. A novel feature for roll control, or the ability to keep the missile from rotating about its longitudinal axis, was the use of the exhaust gases from the turbopumps vented through a nozzle which could be swiveled to counterreact rolling. (This same feature would be introduced as a secret feature on the Jupiter intermediate-range missile produced by von Braun's team at Redstone Arsenal in the United States a few years later— another transfer of technology to both the US and the USSR due largely to the engineering foresight and imagination of Ludwig Roth's advance planners at Peenemünde three or four years earlier.) Path control was accomplished by mounting the engine on a double knife edge or alternately on a ball and socket and moving it with pneumatic or hydraulic actuators.

The warhead compartment was to be separated from the rocket body by explosive bolts, a significant saving in weight over the retro-rockets proposed for the same purpose on the R10. Also, the warhead was to be encased in plywood as a means of insulating it from the heat of reentry into the atmosphere.

While mobile ground launching equipment was proposed for the R14, Gröttrup personally was convinced that it was unnecessary. The advantage that could be gained in moving the missile a few hundred miles from the point where it was manufactured to its launch site was negligible in terms of intercontinental targets. He proposed quite simply, and logically, launching the missile from its manufacturing plant!

Accordingly, Heinz Jaffke and his associate Anton Närr designed an underground factory, similar to Mittelwerk, from which the R14 was to be built and launched. (Jaffke was a talented designer of such structures. He assisted in the design of the first large rocket static-test facility of the Russians outside Zagorsk, some 36 miles northeast of Moscow. In time it included a 220,000-pound thrust test stand, a structure that came in handy when the USSR began planning space missions not too far in the future.) The facility Jaffke proposed could not only manufacture the R14, but it could also extract the oxygen needed from the air and store sufficient quantities of ethyl alcohol for the rockets that were to be launched from an underground silo adjacent to the plant!

On October 1, 1949, the NTS arrived on the island from Nii-88. Along with Gonor and Pobedonostsev was Korolev. They were briefed on the missile design and took away with them all the drawings and reports that had been generated by Gröttrup's task force. Then the Germans heard nothing more of the R14, except that they were asked in the following month to redesign the warhead section to include its kinetic energy in the destructive effect on the target. Work on that project continued through February of the following year. The other task given them was to redesign the rocket body to utilize aluminum rather than steel.

Following these instructions, the Germans received no bonuses, but they also received no criticisms. It is possible that by then the decision had been made to return the Germans to their homeland and that the Soviets simply wanted to gain as much technical data from them as was possible. An alternate approach to developing a missile with a warhead weight of 6,600 pounds and a range of 1,800 miles was followed by a somewhat smaller group on Gorodomlya led by Albring. It was designated R15 and was an unmanned version of the Sänger-Bredt antipodal bomber. With it, an R10 or V-2 booster would send a small, pilotless bomber several miles into the air. There its ramjet engine would ignite and send the craft on to a height of 8 miles, from which it would dive on to the target. Drawings and reports were submitted to the NTS, but nothing more was heard of the project. In 1951, Dr. Joachim Umpfenbach received two tasks that may have been related to developmental work on the R15 or a similar vehicle. One was to design a statoscope, or instrument to maintain a constant height for a vehicle in flight by means of a barometric device, such as had been used on the V-1. The other task was the design of a gyroscope using the concept of an oscillating pendulum instead of a rotating mass.

— — —

There were other rocket projects on which the Germans worked piecemeal. The Soviets showed interest in an antiaircraft rocket similar to the Wasserfall. A small group at Nii-88, under the direction of a Soviet engineer named Silnishnikov, was employed on such a weapon. There was also a test stand for the Wasserfall engine located at Nii-88. Karl Harnish, a former Peenemündian with a master's degree in engineering, was involved briefly in the static firing of the engines at Nii-88. Additionally, Albring and Hoch, at Gorodomlya, were asked to produce Taifun drawings, and a few engines were made in the shops at Nii-88 and static-fired there, too. Also at Nii-88 a Soviet engineer named Rashkov had a small group that was studying the Schmetterling antiaircraft missile. Two Germans, Dr. W. Quessel and Karl Falkenmeyer, assisted him for a short time.

In the summer of 1949, Gröttrup was asked by Spiridonov if the German group could undertake the design of an antimissile missile. Considering the time being spent on the R14, Gröttrup said no, and added that he felt such a rocket was too far beyond the technology of the day. Apparently, it was a passing fancy at the time; Spiridonov never brought the subject up again.

Following the completion of the studies on the R10, Rl4, and R15, life on Gorodomlya became stultifying at best. Some ideas of conditions there can be gleaned from Irmgard's diary:

28.7.1949. We live surrounded by water; there is even an inland lake, but we have no drinking water. The water from the tap comes out dirty, full of seaweed and tiny animals.... The atmosphere is very tense and unpleasant....

5.8.1949. for most houses here have raw floorboards with wide cracks. The advantage of these is that the dirt can be brushed straight into the cracks; on the other hand, you can't get rid of the bugs.

13.4.1950. The days seem to drag on. These long nights painfully increase my longing for home and freedom....

20.4.1950. Mrs. R. [Rebitzki] had a nervous breakdown and was taken to the clinic at Kalinin. She has been forced to have her haircut, sit around with fifty insane women and to eat miserable food out of tin bowls.

That petty squabbling and marital infidelity occurred among the Germans was predictable, if, indeed, not understandable under the circumstances. That many of the talented and frustrated men turned to vodka once the stimulus of constructive and challenging work had been denied them was equally predictable. For some, infidelity and vodka were not strong enough measures. Mrs. Engelhardt Rebitzki hanged herself, and an engineer named Möller wandered out in the snow to accomplish the same end, only to be found in time; he lost both hands to frostbite. Similar things happened in other German collectives. By the summer of 1954, when Dr. Brunolf Baade, former chief engineer of the Junkers Aircraft Company, returned to Germany with the remainder of his original team of eight hundred men and their families, twenty-five had died in the USSR, five had committed suicide, and two had gone insane.

On December 2 1, 1950, Gröttrup was relieved as chief of the German collective. Previously, it had been agreed among the Germans that they would do no more work for the Soviets. Taking a leaf from the texts of their masters, the Germans were going to show strength through solidarity. On that day, Ustinov sent his deputy to Gorodomlya with a new set of tasks. Seeking a way of refusing to comply, the Germans hit upon the idea of refusing on grounds of health hazards. The new project required the use of nitric acid rather than oxygen as a propellant. It would give off exhaust fumes that were poisonous.

However, a small fraction of the Germans decided to break ranks, defecting to the Soviets. Once they did, the deputy minister announced that Gröttrup was no longer in charge. Dr. Johannes Hoch was appointed to fill his position and moved to Moscow, where he worked for five years until his death there.

— — —

In contrast to the primitive domestic accommodations that the Ger mans had found on Gorodomlya in 1946 were the island's engineering facilities. There was a Mach 5 wind tunnel and a fully instrumented static test stand for liquid propellant engines with thrusts up to 17,600 pounds.

Additionally, there was an excellently equipped high-frequency laboratory for the electronics and communications specialists. The Soviets also provided the best of scientific instruments for their German tutors—which was, in effect, what they were to become. It was increasingly apparent to Gröttrup, after his arrival in 1948, that the primary function of Branch No. 1 of Nii-88 was pedagogical.

With the beginning of 1951, there was an influx of young Russian engineers just out of the technical universities. They were eager to learn from the Germans; and they were polite, friendly, and appreciative as well. However, the Germans had long since lost their motivation and enthusiasm. While a few tasks related to the R14 continued to come from Nii-88, they received only half-hearted attention. Most of the men had given up hope of ever seeing Germany again.

Then, with the sly perversity shown o n so many occasions, the Russians announced that the first group of twenty Germans would be leaving for their homeland on March 21, 1951! The people in this group were all technicians and thus most easily dispensed with.

To his further humiliation and discomfort, in September Gröttrup was required to give up his small house, t he only one on the island with an indoor bath, and to move into a smaller apartment. In February of the following year, he fell seriously ill. For a fort night he was comatose, and his temperature rose alarmingly. It took two and a half days before the local feldsher (medical technician) appeared. She made him comfortable, gave him some caffeine, glucose, and penicillin. Apparently the last drug turned the tide. Gröttrup recovered, but was not in really good health for well over a year.

By mid-1952, the young Soviet engineers were still arriving on the island. They began taking over more and more of the work of the Germans, utilizing them only as a sounding board for their own ideas and for technical approaches to problem solving. Concomitantly, the tasks assigned to the Germans grew fewer and increasingly unrelated to rocketry. G röttrup was asked by the university in Leningrad to design a computer for controlling a lens-grinding machine. Colleagues who had worked so dedicatedly on the R10, R14, and R15 found themselves designing a vehicle that could skim across the surface of ice-covered bodies of water. By then, the Germans knew that they were being replaced with native talent.

But what would be their fate?

On June 15, a commission arrived from Moscow. After a long conference with the men of the island, the news was released to the women and children. All but twenty of Branch No. 1 of Nii-88 would be returned to Germany on June 21. Gröttrup was among the twenty designated to stay.

With the death of Stalin on March 5, 1953, the Russians on the island all seemed in agreement that the remainder of the Germans would soon be on their way home too. Yet when the men reported for work on that day, expecting a national day of mourning, they were told: «Comrades, let's honor the dead by working harder than ever!» Disheartened and gloomy, they turned to their dull tasks.

But rumors kept cropping up that they would be repatriated. On November 15, the commission from Moscow returned. Their statement, read to the German engineers, was explicit: «All German specialists with the exception of twelve are to return to their country on November 22, 1953. They must leave within two days of that date. We take this opportunity to express our thanks for the work done.»

Gröttrup’s name was not among the twelve to stay.

The dozen who stayed were all specialists in rocket guidance. Under a Dr. Faulstich, they were removed to Moscow and given five-year contracts with good salaries and excellent accommodation. Thus, by the end of 1953, the Russians felt confident in their own competence in the areas of propulsion and structures; but they still were not so confident of their expertise in guidance and control. On November 28, 1953, Helmut and Irmgard Gröttrup, with Ulli and Peter, crossed the river Oder into Frankfurt-an-der-Oder, «the river which to us is the frontier between two worlds, between past and future,» as Irmgard later put it.

After seven years, the majority of the men of Institut Rabe and Zentralwerke were home. In five more years, the remainder would also return.

What had the Russians gained from them?

In the final analysis, they certainly had obtained some talented men from Peenemunde, although by no means in the numbers that the Americans had Scientists and engineers such as Gröttrup, Magnus, Umpfenbach, and Viebach were without doubt of assistance to them in specialized areas. However, such professional talent must be cultivated and motivated if it is to be optimally productive. Clearly, the Soviets did not realize this fact or were consciously unwilling to do so.

As a result, the Russians deprived themselves of many valuable and creative contributions that these men could have made to Soviet rocketry at a very crucial point in its postwar development. Fundamentally, the Russians failed to realize that the team approach or «systems engineering» technique was what had produced the V-2, while their own engineers could produce only the small, solid-propellant katyusha. In compartmentalizing the Germans and fragmenting their efforts and skills, the Russians wasted a great engineering potential.

Despite this treatment of the Germans, the Russians took what they had learned from them and quickly put it to use. Men such as Sergei P. Korolev, Valentin P. Glushko, and Aleksei M. Isayev (a designer of rocket engines) who had nothing to gain from the Germans in theory quickly absorbed their engineering and managerial techniques and then went on to form teams to build the rocket boosters that sent the first spacecraft into orbit about Earth and scientific probes to the Moon, Venus and Mars.

|