|

|

|

|

|

Troy Hallsell

© Troy Hallsell. 2022.

Our address: en@rvsn.info |

|

See also: |

| |||

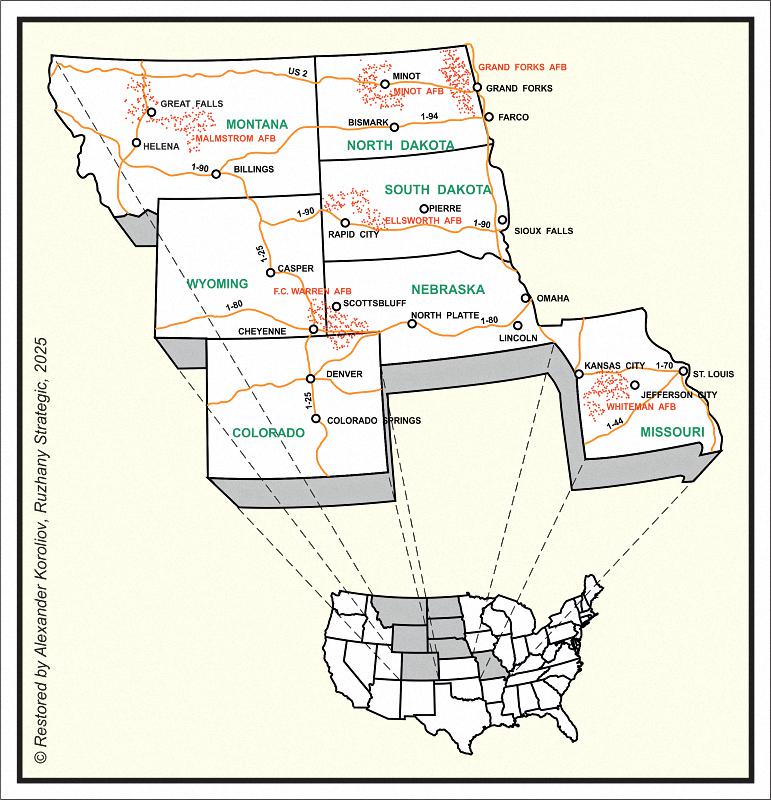

| The Great Plains hosted the Minuteman Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBMs) in several US Air Force missile wings. The ICBMs formed one component of the nuclear triad, which also included submarine-launched missiles and airplane bomber fleets. National Museum of the US Air Force Restored by Alexander Koroliov. |

As the Department of Defense (DoD) sought to reduce its military footprint, Great Falls’ civic and business leaders lobbied to retain the Minuteman III (MM III) ICBMs and an air refueling mission at Malmstrom AFB. With about a third of Great Falls’ economy at stake, the consequences were grave. First, in response to the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START), Montana’s congressional delegation and Great Falls area residents found themselves in a political fight with North Dakota over the MM IIIs at Grand Forks AFB. Second, boosters lobbied to keep Malmstrom AFB open and to retain its air refueling mission during the 1995 Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) process. Ultimately, Malmstrom’s supporters could not convince the DoD to change its recommendation to move the tanker mission to Florida. When Malmstrom’s supporters rallied to prevent the DoD from closing the installation throughout the 1990s, they revealed to anyone watching that Great Falls was a municipality dependent on federal defense spending for its survival — and they would not go down without a fight.[3]

The end of the Cold War hit the defense industry the hardest, affecting military communities and manufacturing hubs. Great Falls’ attempt to retain Malmstrom AFB’s military missions and save the base from closure was similar to efforts in other towns and cities around the nation. Around the country, members of the Cold War coalition, an informal, wide-ranging group of voters and elected officials who looked “to military spending... to alleviate unemployment and economic turmoil,” came together to mitigate the impact the post–Cold War drawdown had on their local economies. McDonald Douglas laid off hundreds of employees at its St. Louis headquarters and nine thousand workers across the country. In southern California, Lockheed Aircraft laid off seven thousand employees. Pennsylvania’s congressional delegation successfully defended the V-22 Osprey rotary aircraft program — despite the DoD’s objections — that employed six hundred workers at a Boeing plant outside of Philadelphia. In Connecticut, Representative John G. Rowland worked with UNC Naval Products to get the company another contract.[4]

Many military communities resigned themselves to base closures and sought ways to revitalize or transition their economies. Instead of fighting tooth and nail to keep Fort Ord open, Seaside, California’s civic and business leaders, along with elected officials, developed a regional redevelopment plan. Their plan leveraged the region’s beautiful location and climate along the Pacific Ocean to develop a golf tourism industry. It also brought a new California State University campus to the shuttered Fort Ord and promoted its hiking and mountain biking trails. In rural South Dakota, farmers and ranchers organized to ensure the deactivation of the 44th Missile Wing’s Minuteman II ICBMs did not contaminate the region’s groundwater. While agricultural producers’ bottom line was not directly tied to the ICBM mission, their water was. Like other military communities around the nation, rural South Dakotans did their part to mitigate the impact of the Cold War’s end on their daily lives.[5]

| |||

| An aerial view of Great Falls Army Air Base’s runway complex in the early 1940s. Great Falls had difficulty recovering from the aftershocks of the Great Depression until the mobilization for World War II. The U.S. Army Air Corps’s decision to locate two bases in Great Falls proved a boon, as the construction of Great Falls Army Air Base created thousands of jobs. 1999.053.0003, The History Museum, Great Falls |

Great Falls’ economic relationship with Malmstrom’s Cold War infrastructure was fundamentally similar. Malmstrom and Great Falls had a deeply intertwined economic relationship that began with the mobilization for World War II. Long dependent on north-central Montana’s agricultural economy and smelting, on the eve of U.S. entry into World War II, Great Falls was struggling to pull itself out of the Great Depression. Given the projected wartime spending, city leaders lobbied the Army Air Corps to locate an air base at Great Falls in the summer of 1940. The city made an attractive location, given its proximity to five hydroelectric dams, a transcontinental railroad, and an easily accessible labor force. After intense lobbying from the city’s boosters, the Army Air Corps stationed the 7th Ferrying Group at the municipal airport on Gore Hill west of town. From there, the group transported war materiel to the Soviet Union via Fairbanks, Alaska Territory, as part of the Lend-Lease program. It also located a B-17 bomber training mission on what would later become Malmstrom AFB six miles east of Great Falls. As historian William J. Furdell points out, Great Falls residents “embraced the economic benefits brought by wartime demands for what local farms and factories could produce, and by the employment and contracting opportunities [Malmstrom AFB] generated.” In 1942, the Army Corps of Engineers hired approximately 2,500 workers who labored twenty-four hours a day for ten months to build Great Falls Army Air Base. Combined with the addition of approximately 4,000 uniformed and civilian personnel, this economic activity helped Great Falls grow in population by over 30 percent, from 29,928 in 1940 to 39,006 in 1950. It was a stunning reversal of Depression-era fortunes thanks to military spending.[6]

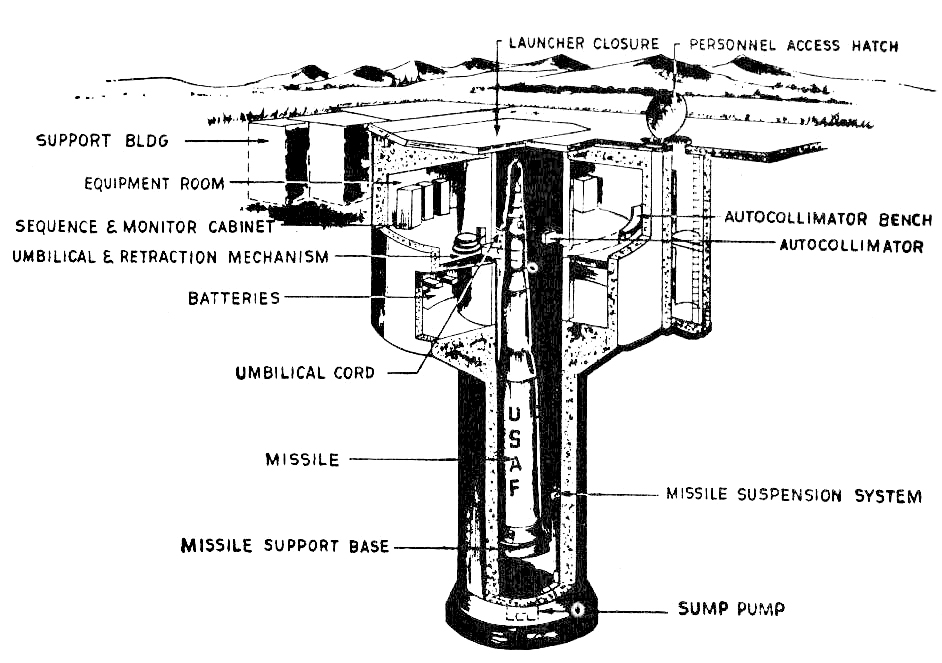

This economic relationship became more entwined as the Cold War deepened. The Air Force selected Malmstrom AFB as the home of the 341st Strategic Missile Wing (341 MW) in 1960. The installation of the new Minuteman ICBM weapon system required the construction of fifteen missile alert facilities, fifteen launch control centers, and 150 launch facilities (LF) spread across 13,800 square miles in seven central Montana counties: Cascade, Chouteau, Fergus, Judith Basin, Lewis and Clark, Teton, and Wheatland. While the DoD issued approximately $50 million in construction contracts, it expected the project to spark $330 million of economic activity across its 2.5-year lifespan. The Minuteman required the DoD to build and maintain roads throughout the missile fields for the transport of the ballistic missiles and warheads. Cascade County received 120 miles of improved roads alone.[7]

| |||

| A diagram of a Minuteman launch facility and missile. Buried underground and shrouded with a thick concrete cover, the Minuteman system was designed to survive a nuclear strike, offering a retaliatory option in the logic of nuclear policy. National Museum of the US Air Force |

The project brought two hundred new housing units to Lewistown and provided high-paying jobs to area workers. Jack Gannon’s experience was typical: he left his job at a local tire shop making $1.75 per hour for $5.75 per hour—a 400 percent wage increase—as a quality assurance inspector for Ets-Hokin, a contractor that laid 2,100 miles of communication cables across central Montana. This infusion of federal spending led journalist Murray M. Moler to proclaim the ICBM program was “the darnedest thing to hit Montana since they found copper in Butte Hill.”[8]

From the 1950s through the 1980s, Malmstrom hosted numerous flying, radar, and Minuteman upgrade missions. It hosted air refueling missions since the early 1950s. On December 18, 1953, the Air Force activated the 407th Air Refueling Squadron within the 407th Strategic Fighter Wing to support its long-range bomber escort missions. It flew KB-29s and, later, KC-97s, before Strategic Air Command (SAC) folded it into the newly activated 4061st Air Refueling Wing in July 1957, which was deactivated in 1961. In 1988, the Air Force brought the refueling misison back to Malmstrom when it reactivated the 301st Air Refueling Wing and its KC-135R Stratotanker mission, bringing nearly seven hundred military and civilian positions to the base.[9]

In 1957, the Semiautomatic Ground Environment (SAGE) radar system became operational at Malmstrom AFB. It was a network of large computers that collected data from radar sites and processed it to create a single image of the airspace over a specific sector. The North American Air Defense Command (ADC) used SAGE to direct and control its response to a manned Soviet invasion into North American airspace. For example, if SAGE detected an incoming aircraft, ADC scrambled aircraft from the 29th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron at Malmstrom to intercept it. Malmstrom’s SAGE was responsible for the Great Falls Air Defense Sector beginning in February 1961 until the Air Force deactivated it on June 30, 1983.[10]

In August 1964, the Air Force announced it would construct an additional ten launch control centers and fifty launch facilities to house Malmstrom’s new Minuteman IIs. Construction began on the 564th Strategic Missile Squadron’s (564 MS) missile fields in March 1965, and finished in the fall of 1966. SAC declared the 564 MS operational the following April. In 1967, 341 MW also began the force modernization program to replace the Minuteman I ICBMs with Minuteman IIs throughout the wing. From the 1960s through the 1980s, 341 MW also hardened its LFs, making them more resistant to Soviet offensive weapons; upgraded its command and control system; executed the Minuteman Integrated Life Extension program to extend the weapon system’s life until 2005; and upgraded the Minuteman’s propulsion system, which further extended its service life until 2020. These missions and upgrades made Malmstrom AFB an integral location in the nation’s defense and central to Great Falls’ economy through the end of the Cold War.[11]

| |||

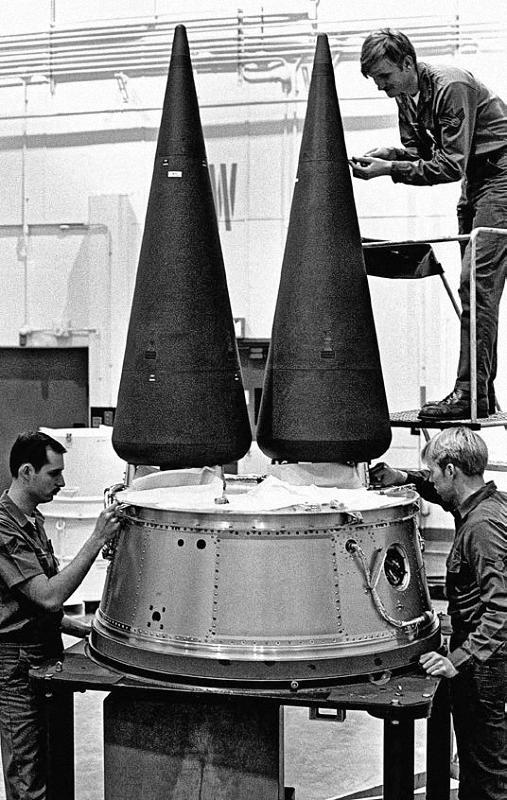

| Airmen perform maintenance on the warheads and reentry vehicle of a Minuteman missile in the 1970s. National Museum of the US Air Force |

Treaty-based nuclear drawdown was the first threat to Great Falls’ economy. Given the Soviet Union’s diminished threat to U.S. national security and the waning Cold War, Presidents George H. W. Bush and Mikhail S. Gorbachev signed the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) on July 31, 1991. After the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945, and the USSR detonated its first nuclear bomb in 1949, nuclear weapons had become a staple of Cold War defense policy. The geopolitical turmoil of the 1960s, including the 1961 Berlin Crisis, the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, the Vietnam War, and the 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, “left policy makers increasingly open to cooperative measures that limited the dangers of competition.” From 1969 to 1983, the United States and the USSR engaged in a continuous set of negotiations regarding nuclear arms control. Once the collapse of the USSR ended the Cold War, both sides wanted to reduce the size of their respective arsenals.[12]

START called for the gradual reduction of strategic arms over the next seven years. The United States, Russia, and other former Soviet Republics agreed to reduce their nuclear arsenals to 6,000 warheads and limit launch platforms to 1,600, including ICBMs, submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and long-range bombers. President Bush called START “a fundamental milestone in reducing the risk of nuclear war, stabilizing the balance of strategic forces at lower levels, providing for significant reductions in the most threatening weapons, and encouraging a shift toward strategic systems better suited for retaliation than for a first strike.” It also permitted the United States to leverage this “peace dividend” into greater national security by reducing defense spending. During a September 27, 1991, address, Bush announced that as a result of the agreement the Air Force would take all 450 of its MM II ICBMs at Ellsworth AFB, South Dakota, Whiteman AFB, Missouri, and Malmstrom AFB off alert. Within seventy two hours, Strategic Air Command executed this order.[13]

Shortly after Bush’s announcement, civic and congressional leaders in Montana and North Dakota advocated for their respective ICBM missions. Given Malmstrom’s strategic value, boosters felt the base was in a good position to keep its ICBM mission since it was “the most strategically located missile base and has the most solid missile silos.” Montana’s congressional delegation fought North Dakota’s representatives to speed up the transfer of MM III ICBMs to Malmstrom AFB. In the 1991 defense bill, Senator Kent Conrad (D-ND) inserted an amendment that “required an extensive Air Force report that” analyzed and explained “its force plans before Minuteman III missiles kept in storage could be placed in converted Minuteman II silos at Malmstrom.” He hoped the report would protect Minot AFB from losing its MM III ICBMs and possible closure. Not surprisingly, Senator Conrad R. Burns (R-MT) sent a letter to Secretary of Defense Dick Cheney asking the DoD to speed up the report.[14]

In the House of Representatives, Ron Marlenee (R-MT) neutralized an amendment to the 1993 defense authorization bill by North Dakota representative Byron Dorgan (D-ND) that sought to prohibit the consolidation of the Air Force’s ICBM mission and prevent the transfer of ICBMs from storage or another base. Both Minot AFB and Grand Forks AFB survived this round of nuclear disarmament, with the first thirty Minuteman III ICBMs delivered from Hill AFB in Utah to Malmstrom and the remaining 120 to come from a soon-to-be-named wing.[15]

The Air Force based its decision to keep Malmstrom AFB’s MM III ICBM mission on operational, technical, and logistical considerations. First, its LFs had an average elevation of 3,900 feet, as opposed to 2,600 feet at Ellsworth AFB in South Dakota and 800 feet at Whiteman AFB in Missouri; Malmstrom’s elevation required less thrust to launch an ICBM into space. Second, the 341 MW had “recently received system upgrades to increase hardiness and retargeting capability,” according to historian David Stumpf. To upgrade Ellsworth’s ICBM weapon system would cost an additional one billion dollars on top of the MM III conversion. It did not make financial sense. Third, the 341 MW already had 50 MM III ICBMs on alert in the 564 MS. Therefore, the wing only needed 150 additional MM IIIs to reach a full complement, as opposed to 200 in South Dakota and Missouri. As a result of these factors, the Air Force inactivated the 44th Missile Wing at Ellsworth and 351st Missile Wing at Whiteman and began deactivating their ICBM infrastructure in December of 1991.[16]

Between 1991 and 1998, the 341 MW replaced its MM II fleet with MM IIIs. The wing removed its first MM II from LF J-03 east of Dutton, Montana, on November 13, 1991, in accordance with START. It made steady progress with this effort, and by October 23, 1992, the wing had removed 33 MM IIs from its LFs, with all 150 gone by August 10, 1995. Before the wing installed MM IIIs in the old MM II LFs, it reinforced the headworks to support the heavier MM III during installation and removal operations. The first MM III arrived aboard a C-141 transport aircraft from Hill AFB, and on November 19, 1992, the 341 MW installed it into LF J-09, about twenty miles northwest of Great Falls. The 341 MW completed the initial conversion of the first thirty MM IIIs by June 1994. According to the Tribune, this changeover was “important because it could solidify the missile wing’s future at Malmstrom at a time when the military is consolidating forces and closing bases elsewhere.” This calm would not last.[17]

| |||

| After a series of close confrontations that nearly escalated to nuclear war, the United States and the Soviet Union began engaging in arms control talks, culminating in the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START). Signed by President George H. W. Bush (left) and President Mikhail Gorbachev (right) on July 31, 1991, START called for the gradual reduction of nuclear arms and launch platforms as a part of the post–Cold War de-escalation. P24017–08, George H. W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum |

The next major threat that Malmstrom and Great Falls faced was base closure and realignment, part of the post–Cold War drawdown. On November 5, 1990, President Bush signed the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Act of 1990 into law to reduce the federal budget deficit and streamline the DoD’s operational efficiency. This legislation provided “the basic framework for the transfer and disposal of military installations closed during the base realignment and closure (BRAC) process.” It established the independent Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission (DBCRC) to oversee this effort. The commission claimed, “Base closures must be undertaken to reduce our nation’s defense infrastructure in a deliberate way that will improve long-term military readiness and ensure that taxpayer dollars are spent in the most efficient way possible.” The DBCRC met during calendar years 1991, 1993, and 1995. Based on the DoD’s recommendation, and its own analysis, the DBCRC closed or realigned 110 installations during its lifespan. Its authority expired on December 31, 1995. While the loss of the KC-135R squadron during the 1993 BRAC cycle initially got residents’ attention to the threat posed by BRAC, Malmstrom’s existence was not up for question until the 1995 cycle.[18]

| |||

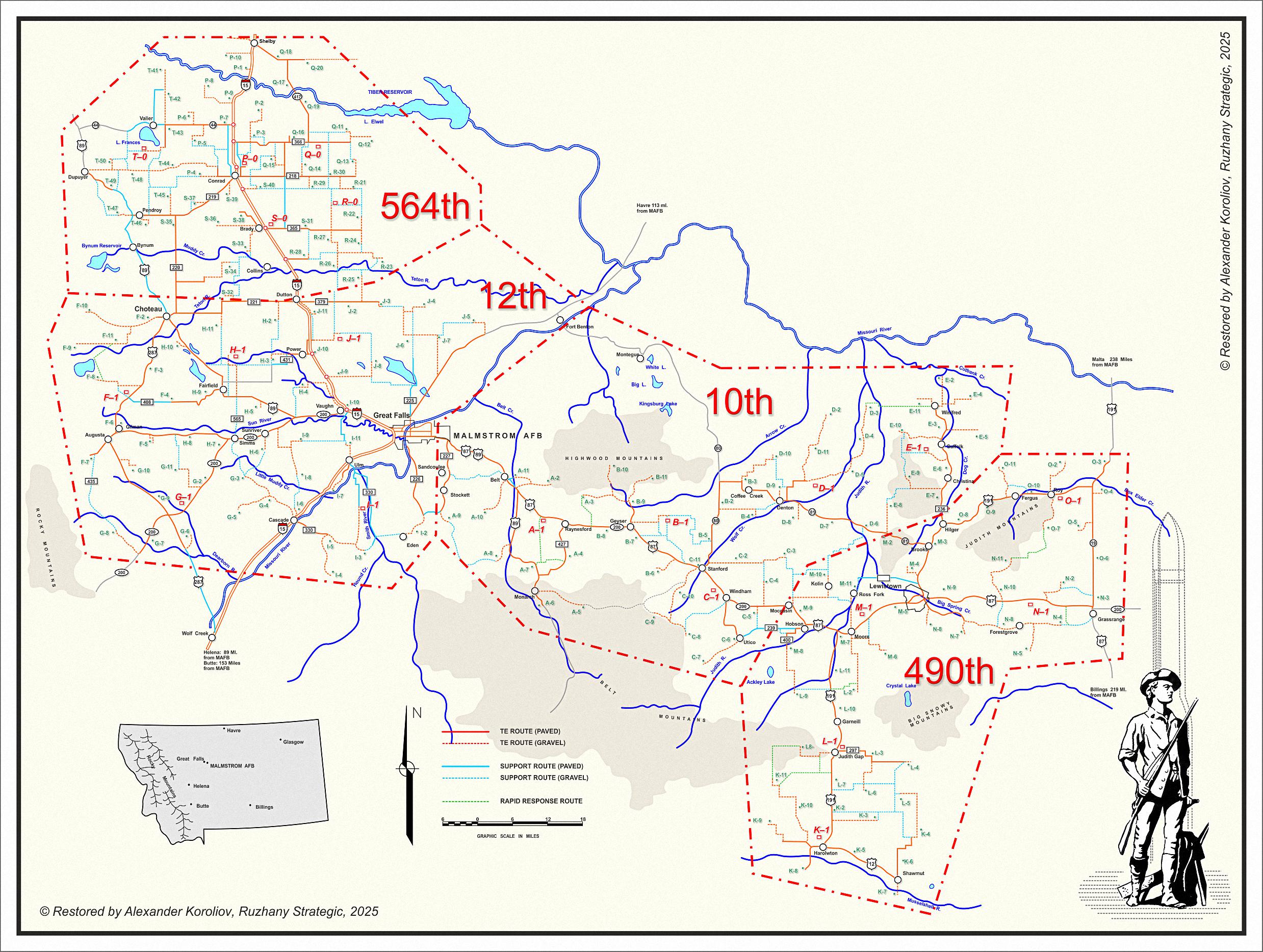

| A 1995 map of the missile fields of the 341st Missile Wing, showing its four squadrons and the access road infrastructure. Beyond the economic impacts on Great Falls, the Air Force’s presence affected much of central Montana, from Shelby to Harlowtown. 341st Missile Wing History Office, Malmstrom AFB Restored by Alexander Koroliov. View full size on new page. |

| |||

| An airman inspects a Minuteman missile in its silo, ca. 1995. Currently, maintaining Malmstrom’s missile fleet requires nearly five hundred personnel, while more than three hundred others are responsible for operations. Several thousand other airmen staff the security forces, medical group, and other operations. National Museum of the US Air Force |

The DBCRC consisted of six members, who had the difficult task of closing up to 15 percent of existing U.S. military installations. The DBCRC reconstituted every two years (1991, 1993, 1995), with the president nominating its members and the Senate approving them. In October 1994, President William J. Clinton nominated former Illinois senator Alan J. Dixon—coauthor of the Defense Base Closure and Realignment Act of 1990—to chair the 1995 committee. The rest of the members came from a cross-section of America’s political, civic, and business leaders.[19]

The DBCRC operated on a set schedule. On March 1, 1995, the DoD sent the commission its recommendations on base closure and realignment. Once received, the DBCRC used three primary criteria to inform its recommendations: military value, return on investment, and impact, with military value carrying the most weight. It could add or remove bases from the Pentagon’s recommendations. Public hearings followed. The DBCRC then submitted its recommendations to the president on July 1, who had until July 15 to approve or disapprove them. If approved, they went to Congress, which had until September 30 to disapprove the recommendations. If not, they became law. Dixon anticipated the 1995 BRAC process would result in “a fairly substantial reduction. . . . That will not be very pleasant.”[20]

| |||

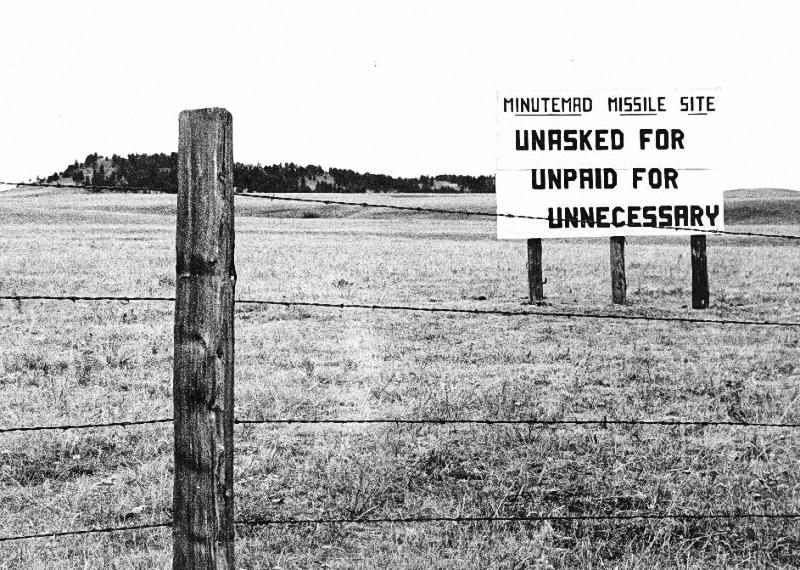

| While Malmstrom’s missiles brought substantial infrastructure and money to central Montana, not everyone agreed with their presence, as this undated protest sign shows. 2002.094.0051a, The History Museum, Great Falls |

Malmstrom supporters expected the installation’s missions to contract, but the question was by how much. The DoD’s 1994 Nuclear Posture Review wanted to keep 450 to 500 MM IIIs on alert. Yet the Air Force had the capacity to place 650 MM IIIs on alert across four wings in North Dakota, Montana, and Wyoming. The DoD would inactivate one of these wings to meet this objective. Even though the 341 MW had only 80 ICBMs on alert since it had halted the LF conversion during the BRAC process, Malmstrom’s backers were cautiously optimistic that the DBCRC would not close the installation. The chamber of commerce and affiliated groups pointed to its top ICBM ranking during the 1991 and 1993 BRAC processes. It noted that the Air Force recently upgraded its base housing and built a new power plant and base medical clinic. To shutter Malmstrom would waste Air Force resources and send economic shockwaves throughout the community, an outcome at odds with the DBCRC’s criteria.[21]

Malmstrom’s supporters were less sanguine about its tanker mission. In 1993, the Air Force sent a squadron’s worth of KC-135R refueling tankers from Malmstrom AFB to Fairchild AFB in Washington. Then the Air Force downgraded the 43rd Air Refueling Wing to a group and transferred its support units to the 341 MW. Additionally, the Air Force noted a tanker deficit in the southeastern United States. Malmstrom’s tanker mission stood on shaky ground. Montana’s congressional delegation acknowledged this possibility.[22]

Any contraction of Malmstrom’s mission would strain Great Falls’ already anemic economy. By the 1990s, the city was reeling from the painful effects of de-industrialization that had decimated extractive and manufacturing economies around the nation. Between the 1950s and 1970s, metal mining declined as a major industry in Montana, especially for copper. As a result, in 1980, Atlantic Richfield closed its Black Eagle refinery, cutting 1,500 jobs. Throughout the 1980s, Great Falls suffered during a statewide recession featuring a sharp downturn in oil and gas profits, cuts to railroad workforces, and a decline in tax revenues that led to a reduction in state services.[23]

| |||

| On September 18, 1982, an economic era came to an end in Great Falls, as Atlantic Richfield demolished its Black Eagle smelter stack. Powered by hydroelectric dams on the Missouri River, metal refining had long been a key component of the local economy, and the detonation of the smelter marked a major shift from highly skilled trades to the service economy and an even greater dependence on military spending. 2011.186.0004, The History Museum, Great Falls |

Likewise, as the hub of Montana’s Golden Triangle, an agricultural region that runs roughly from Great Falls to Browning to Havre, the area suffered from a sharp recession, undercut by President Jimmy Carter’s 1980 embargo on grain sales to the Soviet Union. This was compounded by plummeting grain prices and a series of severe droughts in 1985 and 1988. According to historian Michael P. Malone, “Montana agricultural earnings dropped over $2 billion to around $1.6 billion per year, and land values fell by over one third.” By 1992, most of the state’s jobs had shifted away from agriculture and manufacturing and into service industries. Low skill/ low wage jobs replaced good-paying jobs in manufacturing, mining, and other skilled trades. In 1994, Montana had the nation’s lowest growth rate in per-capita income. Given these dire circumstances, Great Falls boosters sought to preserve its primary source of good-paying jobs on the eastern edge of town. This economic distress made the city more reliant on Malmstrom AFB for its future than ever before.[24]

On the ground, business and civic leaders fought to keep Malmstrom AFB off the BRAC list. Great Falls was part of a large political constituency whose economic livelihood was tied to the defense spending that emerged within the Cold War coalition after World War II. During the post–Cold War drawdown, according to historian Michael Brenes, “Cuts to the defense budget entailed economic anxiety and uncertainty, which [seemingly everyone] sought to avoid at all costs.” In Great Falls, this constituency of business leaders and professionals formed the Committee of 80. Established in 1979, the committee lobbied Congress and the DoD in support of Malmstrom AFB.[25]

The economy was the core of the Committee of 80’s concerns. Malmstrom AFB made up approximately a third of Cascade County’s economic base. Paul Polzin, director of the University of Montana’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research, projected that if the DoD closed Malmstrom AFB in 1995, “it would be an utter disaster, there is absolutely no question about it.” With an economic impact of $276.8 million, the ripple effect could devastate nearly all sectors of Great Falls’ economy. Observers believed a shuttered Malmstrom would prevent the construction of new facilities in town; prospective home buyers would stop looking, while a glut of homes for sale would flood the market causing prices to plummet. The city’s tax base would shrink, meaning less money for roads, schools, and emergency services. Urban blight would follow. According to Tim Ryan, spokesman for the Committee of 80 and head of Great Falls’ Economic Development Authority, “We’re not Johnny-come-latelies to lobbying and community relations since the military began closing bases . . . we’ve been doing it for years.”[26]

Not all residents supported Malmstrom AFB during the BRAC proceedings. Anti-nuclear activists had a consistent presence in central Montana since at least 1978. Much of their activism was part of a broader nuclear freeze campaign throughout the 1980s that sought an agreement between the United States and the USSR to halt the testing, production, and deployment of nuclear weapons. While much of this campaign took place in the halls of Congress, activists also took to the streets and missile fields. In 1992, peace activists held an Easter vigil at Malmstrom AFB’s gate on 2nd Avenue North. While the protest was small, it drew people from around the state. Coming from Ulm, Heidi Bates and her niece waved signs that declared “Kids Need Peace.” Curt Buttons from Butte stepped onto Air Force property, where base security forces greeted him with a handshake before they arrested him for trespassing. Others sang songs like “We Shall Overcome” and gave speeches on the virtues of nuclear disarmament.[27]

In the missile fields, peace activists used different tactics, including nonviolent direct action. On June 5, 1982, at 6:15 p.m., Mark Anderlik and Karl Zanzig threw a carpet over the barbed wire at LF R-29 east of Conrad, Montana, scaled the fence, and spread wheat seeds on the ground in a symbolic attempt to reclaim the agricultural land farmer David Hastings had lost to the Minuteman ICBM program; they then sat on the launcher enclosure door and waited for security forces to arrest them for trespassing. They were members of Silence One Silo, a local group that wanted to rid Montana of a single Minuteman ICBM to start a larger disarming and peace process in the United States. According to Anderlik and Zanzig, they wanted to “show Montanans that we don’t have to be chips in the gamble with our lives.” Over the next three years, the Air Force arrested more than a dozen peace activists at R-29.[28]

That there was a small, vocal contingent of residents that wanted the military out of Montana was not a surprise. In March 1995, Ray Jergeson and Paul Stephens, board members on the Committee of the 90s, an anti-nuclear organization critical of nuclear deployment and DoD policy, advocated for the closure of all military missions at Malmstrom AFB and the Montana Air National Guard at Gore Hill. Given the post–Cold War drawdown and nuclear disarmament, Jergeson asked a simple question: “If the purpose of a mission disappears, why is the mission still here?” They circulated petitions that demanded the federal government shutter Great Falls’ two military missions and convert them to “productive civilian uses.” Jergeson hoped that the DoD would funnel the money saved on defense spending in Great Falls to the nation’s social programs. Not everyone agreed: James Pier of Sun River called their petition “bull——!” He continued, “If the base closes down, who’s going to support this town?” As it turned out, peace activists’ efforts to close the base did not deliver the results they wanted.[29]

With most of the residents and local officials in support of Malmstrom, the Committee of 80, City of Great Falls, Cascade County, and the State of Montana levied a two-pronged attack on the DBCRC to protect Malmstrom AFB from the BRAC process. They hired a D.C. consulting firm, Verner, Liipfert, Lawton, McPherson, and Hand, to prepare their case for Malmstrom AFB locally, and then take their campaign directly to decision-makers in Washington. The firm coordinated local and congressional lobbying efforts, researched Malmstrom and competitive bases, and prepared local officials to give testimony. The Great Falls City Commission budgeted up to $80,000 for this purpose, but sought $25,000 of that total from the Cascade County Commission, along with $5,000 from the chamber of commerce’s Military Affairs Committee and $10,000 from other sources. Governor Marc Racicot asked the state legislature to contribute $20,000 to the effort; the legislature obliged. Given the base’s economic impact to the city and Cascade County, Commissioner John Gilbert argued, “We can’t do enough to protect that part of our economy.”[30]

| |||

| Some anti-nuclear activists took part in nonviolent direct action against the presence of the Minuteman missiles in Montana, including members of Silence One Silo, an organization advocating for nuclear disarmament. On June 5, 1982, activists Karl Zanzig and Mark Anderlik scaled the fence at Launch Facility R-29 near Conrad, and scattered wheat seeds to symbolically reclaim the land. In the following years, Air Force security forces arrested more than a dozen protestors at R-29. 341st Missile Wing History Office, Malmstrom AFB |

When the DoD released its closure and realignment recommendations to the DBCRC on March 1, 1995, Malmstrom’s supporters learned the base was not on its closure list. However, the DoD requested the commission realign its KC-135R tanker mission to Florida. While this allayed residents’ biggest fear, it meant that an estimated 1,013 jobs would leave the area. In response, Senator Burns requested Alan Dixon and other DBCRC members visit Great Falls before they made their final decision on July 1, 1995. The commission scheduled a regional hearing at the Great Falls Civic Center for March 31, 1995, where three of its members would receive and record the public’s comments on the DoD’s recommendations. The importance of this visit was clear to the base’s advocates. “We can’t emphasize enough of the importance of the community making a good showing of support for Malmstrom at this single, stand-alone visit by the commission,” said Terry Pehan, president of the Great Falls Area Chamber of Commerce. Regional hearings like this were the best opportunity for DBCRC members to hear Great Falls’ case for keeping its military missions.[31]

As soon as the DBCRC scheduled its hearing in Great Falls, Malmstrom’s backers gathered to strategize. A steering committee made of twenty-five volunteers from Great Falls’ businesses, community, and government met at the chamber of commerce conference room to research and prepare the testimony that base supporters would give to the DBCRC committee members at the hearing. At the core of its strategy the committee believed “we’ll have to defend the Pentagon decision to move missiles to Malmstrom from another base and attack the decision to move aircraft from Malmstrom.” According to Ryan, they would not directly challenge the Air Force’s decision to move Malmstrom’s tankers to MacDill AFB. Instead, they would fight to keep the runway open; a valid pitch given the Air Force’s $53.5 million investments in flying operations since 1989. The committee believed Montana’s clear flying weather, uncluttered air space, and lack of ground encroachment were selling points too. Boosters felt that “if the Air Force closes the runway, it removes many alternative uses of the base.” Without an active runway they could not lure another flying mission to the area in the future.[32]

Malmstrom’s boosters made their case to the DBCRC on March 31, 1995. Civic leaders and area residents planned a spectacle to greet the commission. Chamber of commerce president Terry Pehan supported the preparations, arguing, “Other smaller base communities in similar circumstances have turned out crowds of 5,000 to 10,000 people, we should do no less in Great Falls.” After the DBCRC members arrived in Great Falls, organizers drove them to the civic center along a route lined with an estimated seven thousand residents bearing posters and flags, cheering loudly in support of Malmstrom. A huge American flag draped the front of the civic center, while student bands from C. M. Russell and Great Falls High Schools performed on the steps. Once inside, high school choir members serenaded the commissioners with their rendition of the “Star Spangled Banner.” Reporter Richard Ecke of the Great Falls Tribune described this display as one loaded with “unabashed patriotism, economic self-interest, genuine gratitude and a few touches of silliness.” Commission member J. B. Davis was awestruck by his reception. “What a marvelous welcome,” he said. “We’re delighted to be here, back in God’s country, the Big Sky. I’d forgotten how beautiful it was.” The moment of truth had arrived.[33]

| |||

| Tim Ryan speaks from the podium at the ground-breaking ceremony for Malmstrom’s power plant in June 1983. Ryan was the spokesman of the Committee of 80 and the head of Great Falls’ Economic Development Authority. He took the lead in advocating for Malmstrom’s continued presence in Great Falls during the Base Realignment and Closure process, coordinating the commissioners’ visit to the civic center, and the lobbying efforts to keep the base operational. 1990.026.0143, The History Museum, Great Falls |

Approximately 1,800 attendees packed the civic center auditorium for the regional hearing. It was a tightly structured event where boosters had thirty minutes to make their case for Malmstrom’s military missions, with fifteen minutes for commissioners to ask questions, followed by ten minutes for public comments. The hearing would last one hour. Tim Ryan was confident the presenters would make the best argument possible. “We’ve done all we can. . . . The research by our consultants has been excellent. We’ve written a strong case. And we have a huge amount of confidence in the presenters who have graciously volunteered to present our arguments.” Malmstrom supporters recruited retired Brigadier General Teddy Rinebarger, former commander of the 341 MW, and retired Colonel Lynn Guenther, former director of operations for the refueling wing, to argue in favor of moving MM III ICBMs from Grand Forks AFB and against transferring the remaining tankers to MacDill AFB.[34]

General Rinebarger emphasized Malmstrom’s geographic and environmental advantages, such as its proximity to the North Pole—over which the ICBMs would fly to strike targets in Eurasia—and its low groundwater table that made Malmstrom a better investment when compared to Grand Forks. For his part, Colonel Guenther asserted that the Air Force should not abandon the millions of dollars of upgrades it had made to the tanker facilities over the past decade, nor close the runway given Montana’s excellent flying conditions and its use among other Air Force and Air National Guard units. Representative Pat Williams (D-MT) summed up their arguments, saying, “There is no better, more efficient missile base in the nation than Malmstrom. . . . There is no refueling wing with better or clearer or more consistent capacity for expansion than here.” He concluded “You will not find a more dedicated or enthusiastic community for a military facility than right here in Great Falls.”[35]

The DBCRC commissioners did not indicate how boosters’ support for Malmstrom AFB would affect their final decision. However, they insisted that regional hearings like this one were important since vital information came from elected officials and community leaders. “Unless you come to a base personally, and just rely on technical reports, you cannot give it its due,” said commissioner Lee Kling. Local support mattered greatly. According to commissioner Rebecca Cox, “When you have a community like this that is obviously very enthusiastic about the base and its people, that makes a difference.” The commissioners still had numerous public hearings on their agenda, and would take the presentation they received and comments by state and area residents under advisement, but stated that it would require strong evidence to overturn the Pentagon’s recommendations. But if the 1993 BRAC was any indicator, commissioners did not make their final decision until the last day of the process.[36]

| |||

| Senator Kent Conrad (D-ND) speaks at the dedication of the University of North Dakota’s Unmanned Aircraft Systems Training Facility that opened on Grand Forks AFB in 2011. As the U.S. military transformed from its Cold War organization, military bases and communities had to find new missions to keep their installations open. Senior Airman Amanda Stencil, photographer. Public Affairs, Grand Forks AFB |

Rather than wait for the DBCRC to make its final determination, boosters took their pitch to Washington in the second prong of their effort to save Malmstrom’s mission. In May 1995, Tim Ryan led a delegation to Washington, D.C., to continue their lobbying effort. Since Ryan believed thirty minutes was not enough time to make their case, the delegation met with DBCRC staffers and other commissioners to discuss Great Falls’ education system, area recreation, and relatively low cost of living. Boosters left these factors out of the March 31 hearing, but were items that Ryan and company argued made the area a great location for military members, their families, and civilian employees. Montana’s congressional delegation also lobbied the Clinton administration to support Malmstrom AFB. Senator Max Baucus (D-MT) spoke with Leon Panetta, the White House Chief of Staff, and Deputy Secretary of Defense John Deutch about supporting the transfer of Minuteman III ICBMs from Grand Forks to Malmstrom. Senator Burns, for his part, “requested and obtained” a letter from Air Force Chief of Staff General Ronald Fogleman that strongly supported Malmstrom AFB. This direct lobbying worked. When the DBCRC voted on bases to close or realign, Malmstrom AFB made the cut. Its tanker mission, however, was not so lucky.[37]

In the end, the DBCRC supported the Pentagon’s recommendations regarding Malmstrom AFB. First, it opted to keep Malmstrom AFB open and its ICBM mission ongoing. This decision required the inactivation of the 321st Missile Wing at Grand Forks AFB and the transfer of its 120 MM III ICBMs to Malmstrom. The commission made this determination since North Dakota’s higher water table reduced the weapon system’s survivability and required onsite maintenance to counter water intrusion. The wing also had the lowest missile alert rate among all the ICBM wings. Finally, Admiral Henry G. Chiles Jr., commander-in-chief, U.S. Strategic Command, stated that Malmstrom had a higher strategic value given its 200 LFs, as opposed to the 150 at Grand Forks AFB. Second, the commission recommended moving the 43rd Air Refueling Group to MacDill AFB, Florida, and closing Malmstrom’s runway to all fixed-wing aircraft. The DBCRC justified this action given the saturation of KC-135 aircraft at Fairchild AFB in Washington and the shortfall of tanker support in the Southeast. This action had a one-time cost of $26.2 million, with an estimated annual savings of $4.2 million, meaning the Air Force would see a return on this investment in five years. The Air Force closed the runway in January 1997. Once President Clinton accepted the DBCRC’s recommendations and Congress followed suit, they became law.[38]

Ultimately, Malmstrom’s supporters had mixed feelings about the DBCRC’s decision. John Lawton, Great Falls’ city manager, “always knew it would be an uphill battle to get the closure commission to go against the Defense Department recommendation to shift the tankers... but we were able to secure the missiles.” Reverend Phillip Caldwell of Mount Olive Christian Fellowship noted that losing 780 families from the tanker mission “will have a major economic and social impact on our town.” For others, keeping the ICBM mission was the best news that came out of Washington. According to Ryan, it meant Malmstrom was “very secure as a missile base . . . and that gives our base more stability than many others in the Air Force.” While Great Falls residents had mixed feelings on this round of BRAC closures, many did agree on one aspect of its outcome: it was time to start diversifying the city’s economy.[39]

With Malmstrom saved, boosters got back to recruiting federal dollars to Great Falls by bringing in two new missions. Tim Ryan believed there was potential for new military missions to move into some of the 43rd Air Refueling Group’s recently vacated facilities. In September 1996, Senator Burns announced that the Air Force would bring 282 activeduty personnel to Malmstrom AFB as part of the 819th Rapid Engineer Deployable Heavy Operational Repair Squadron Engineer, or REDHORSE, during fiscal year 1998. This unit trained at and deployed from Malmstrom for overseas duty, where its airmen would do heavy construction such as building or repairing roads, runways, utilities, temporary housing, and offices in areas without infrastructure during humanitarian efforts or times of war.[40]

As chair of the Senate Science, Technology, and Space subcommittee, Burns also secured Malmstrom AFB as a test site for the National Aeronautical Space Administration’s (NASA) X-33, a half-size prototype for a future Reusable Launch Vehicle and possible successor to the space shuttle. Once engineers at Lockheed Martin developed the spacecraft, NASA would conduct thirteen of fifteen test flight landings at Malmstrom AFB. NASA slated the test flights to finish in 1999. While these two missions would only replace a fraction of the jobs lost due to BRAC, Senator Burns reassured Great Falls residents that he would “continue to look for new missions for Malmstrom to help offset losses suffered by the community from realignment.”[41]

Malmstrom’s boosters did not have much of a reprieve before the DoD sought to reduce the 341 MW’s mission once more. The Pentagon’s 2005 Quadrennial Defense Review called for a reduction in the MM III ICBM force from 500 to 450. The Air Force stated it would inactivate the 564 MS and deactivate its missile fields as a cost-saving measure; as the “odd squad,” it used a different internal communication network from the other three squadrons and therefore the 341 MW maintained two sets of training equipment, instructors, and maintenance personnel to keep this unit on alert. Malmstrom’s boosters got back to work lobbying Air Force and DoD leadership to keep the 564 MS alive. Representative Denny Rehberg (R-MT) introduced a resolution that supported maintaining all the MM III ICBMs at Malmstrom AFB, while Senators Jon Tester (D-MT) and Max Baucus (D-MT) worked the Pentagon from the upper chamber. However, local supporters resigned themselves to the 564 MS’s closure. Instead of fighting to keep this mission, local government and business leaders sought federal funds to spur private development to mitigate any economic loss. According to Great Falls mayor Dona Stebbins, “The announcement gives us the impetus to band together and prepare a strategy to mitigate its impact.”[42]

As for the deactivation of the 564 MS, the 341 MW methodically carried out the Air Force’s orders. First, the Air Force conducted an environmental assessment on the 564 MS’s ICBM removal and missile field deactivation and determined this action would not adversely affect the environment. On July 2, 2007, Colonel Sandra Finan, the 341 MW commander, announced the deactivation process. On July 12, 2007, the wing removed the first MM III ICBM from LF S-38, northwest of Brady. By July 28, 2008, the wing had removed all fifty missiles. The following month the Air Force inactivated the 564 MS. Colonel Fred Leich (ret.) was one of the squadron’s first crewmembers when he arrived at Malmstrom AFB in the mid-1960s. He said, “I was sad to see my old squad deactivated. . . . But I’m glad we’ve arrived at a point in history where we no longer need as many [missiles].” On February 5, 2011, the New START entered into force. As part of the treaty, the wing eliminated all fifty of the 564 MS’s LFs. On February 11, 2014, contractors began demolition of the 564 MS missile fields starting with LF R-23 near Brady. On August 5, 2014, the 341 MW demolished the last of the squadron’s LFs, T-49, located approximately twenty-five miles west of Conrad, and brought the post–Cold War era in central Montana to an end.[43]

An official portrait of Senator Conrad Burns (R-MT) in 2005, during his final term in office. A tireless proponent of Malmstrom AFB during the Base Realignment and Closure process, Burns fought unsuccessfully for Malmstrom’s refueling mission and successfully for its missiles. After the 1995 DBCRC kept Malmstrom open, he brought the 819th REDHORSE squadron to the base and advocated for using Malmstrom to test NASA’s X-33 prototype. U.S. Senate Historical Office |

|

||

Great Falls’ experience during the 1995 BRAC process provides a cautionary tale for cities that rely too heavily on military spending for its economic well-being. Throughout the Cold War, Congress spent heavily on national defense. In central Montana this included Malmstrom AFB’s flying, air defense, and Minuteman ICBM missions. While many Montanans supported high levels of defense spending, when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991 residents found themselves responding to international events outside of their control. Great Falls’ leaders chose the military as the city’s primary economic driver, responding to the incentives of federal defense spending. In so doing, they further tied Great Falls to international affairs. Beyond international grain and metals markets, Great Falls’ economic survival depended on the existence of antagonistic nuclear powers.

In response to the BRAC process, the Committee of 80 reemerged as a vocal supporter of Malmstrom AFB and the Air Force. It lobbied officials in Washington to keep the base open and Malmstrom’s missions ongoing. At first glance it appeared they were successful; the DBCRC kept Malmstrom AFB open and its Minuteman ICBM mission ongoing—but Malmstrom AFB did lose its air refueling mission. However, it is important to note that the Air Force had ranked Malmstrom at the top of the list of ICBM installations—it appeared the Air Force wanted to keep it open. The Committee of 80 and its allies may have played a role in saving Malmstrom from closure, but that momentum could have very well swung in the other direction. Had the Air Force ranked Malmstrom lower on the list and wanted it closed, no amount of lobbying could have changed its fate. While Great Falls’ boosters have not yet fully replaced the personnel lost to BRAC, they have not stopped trying. As late as July 12, 2019, Montana’s congressional representatives sought to repair and reopen Malmstrom’s shuttered runway with the hope of bringing a flying mission back to Montana. With so much of the region’s economy still based on defense spending, Great Falls’ economy remains at the whims of political calculations in Washington, D.C., and of larger geostrategic forces.[44]

| |||

|

An artist’s rendering of NASA’s X-33 Venture Star Reusable Launch Vehicle, a prototype spacecraft designed to replace the space shuttle. Manufactured by Lockheed Martin, NASA agreed to conduct thirteen of its fifteen test flight landings at Malmstrom AFB until the program’s cancellation in 2001. 9610538, NASA Office of Communications |

There are changes on the horizon though, with plans for economic diversification. In 2020, Congress passed the Great American Outdoors Act, which provided $9.5 billion over five years to address a backlog of maintenance projects on the nation’s public lands, forests, and parks; federal public lands comprise 29 percent of Montana, so some economic growth is likely. Legislators, advocacy groups, and residents alike anticipate improved infrastructure on public lands to lead to increased tourism, and therefore increased revenues into state coffers. Hoping to capture its share of tourist dollars, the Great Falls Development Authority branded the city as “Montana’s Basecamp,” touting Great Falls’ proximity to outdoors activity in Glacier National Park, the Bob Marshall Wilderness, and Showdown ski area. In 2021, out-of-state visitors spent an estimated $65.1 million in and around Great Falls. Great Falls has also grown into a regional medical hub, home to Benefis Health Systems and Great Falls Clinic. Recently, Touro College Montana broke ground on a new osteopathic medical school. Not only will this school provide an array of construction jobs in the near term, but by bringing in five hundred students and faculty, the new school will provide indirect employment in housing, skilled trades, and service industries in the future. This infusion of funds should create some economic buffers for Great Falls if military investment decreases.[45]

|

|||

| During the deactivation of the 564th Missile Squadron’s missile fields, the 341 MW removed all the Minuteman III ICBMs from the squadron’s launch facilities. Pictured in August 2014, workers demolish LF T-49, located west of Conrad. T-49 was the final launch facility of the 564 MS to be demolished in accordance with the 2011 New START. Public Affairs, Malmstrom AFB. |

In the near term, Malmstrom AFB appears to be safe from closure. Since President Joseph R. Biden took office in 2021, the DoD moved forward with Sentinel, a new ICBM weapon system to replace the fifty-year-old Minuteman III. Not only would a new ICBM save taxpayers approximately $482 million per year in maintenance costs, but it would also reinforce the nation’s triad of nuclear-capable bombers, submarines, and ICBMs in the face of China’s expansion of its own nuclear stockpile and Russian president Vladimir Putin’s threats to use nuclear weapons against the United States and its European allies in the wake of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. DoD leadership argues that a new ICBM would “deter Russia, China, North Korea, or any other nation from ever thinking about launching a preemptive attack on the U.S. In the macabre logic of nuclear war planning, those nations are restrained from doing so out of fear that the Minuteman IIIs will unleash their own destruction.” With Sentinel construction scheduled to begin at F. E. Warren AFB, with Malmstrom to follow, and a service life until 2075, communities around these missile bases see economic opportunity once again. Nuclear deterrence is here to stay, and with it, Malmstrom AFB’s contribution to Montana’s economy. Reflecting on the post–Cold War drawdown in central Montana, Tim Ryan perhaps summed up the outcome best: “I think it could have been worse.”[46]

|

|||

Troy A. Hallsell is the 341st Missile Wing historian at Malmstrom AFB, Montana. Before coming to the Air Force as a government service civilian, he served in the U.S. Army from 2005 to 2010 as an all-source intelligence analyst. After a stint at the National Ground Intelligence Center, he earned a PhD in history from the University of Memphis in 2018. He is a podcast host for New Books in the America West, a channel on the New Books Network, and the author of several articles on federal infrastructure projects and urban parks. His book The Overton Park Freeway Revolt: Place, Politics, and Preservation in Memphis, TN, 1955–2017 is under review by the University of Tennessee Press. The ideas expressed in this article do not represent the 341st Missile Wing, U.S. Air Force, or Department of Defense.

Notes

Abbreviations used in the notes include Montana Historical Society Research Center and Archives, Helena (MHS); and Montana The Magazine of Western History (Montana). Unless otherwise noted, newspapers were printed in Montana.

- John Lewis Gaddis, The Cold War: A New History (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), 256–57. For an overview of the Cold War, see Gaddis, The Cold War; Odd Arne Westad, The Cold War: A World History (New York: Basic Books, 2017). “World leaders applaud Gorbachev’s triumphs,” Great Falls Tribune, Dec. 26, 1991; “Our Opinion: Gorbachev gone; future uncertain,” Great Falls Tribune, Dec. 26, 1991.

- Military-dependent municipalities were particularly pronounced in the West. See Roger Lotchin, Fortress California, 1910-1961: From Warfare to Welfare (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1992); Gerald D. Nash, The American West Transformed: The Impact of the Second World War (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 1990); Gretchen Heefner, The Missile Next Door: The Minuteman in the American Heartland (Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 2012), 194; Michael Brenes, For Might and Right: Cold War Defense Spending and the Remaking of American Democracy (Amherst: Univ. of Massachusetts Press, 2020), 4.

- On the Air Force’s post–Cold War restructuring, see William T. Y’Blood, “Metamorphosis: The Air Force Approaches the Next Century,” in Winged Shield, Winged Sword: A History of the United States Air Force, ed. Bernard Nalty (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1997), 2:513–54.

- Brenes, For Might and Right, 4, 222–25.

- For examples of other communities’ response to the post–Cold War drawdown, see Brenes, For Might and Right, 222–39; Heefner, The Missile Next Door, 168–206; Carol Lynn McKibben, Racial Beachhead: Diversity and Democracy in a Military Town (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Univ. Press, 2011), 211–68.

- Malmstrom AFB went by Great Falls Army Air Base and Great Falls Air Force Base between 1942 and 1955. I refer to the installation as Malmstrom AFB throughout this article to avoid confusion. William J. Furdell, “The Great Falls Home Front during World War II,” Montana 48:4 (Winter 1998): 63–75. On the Lend-Lease program, see David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1999), 426–34. Troy A. Hallsell, “B-17 Training and the 7th Ferrying Group at Great Falls Army Air Base in World War II,” Air & Space Power History 69:1 (Spring 2022): 7–14; “1950 Census of Population Preliminary Counts: Population of Montana by Counties, April 1, 1950,” Jul. 31, 1950, (source), accessed Mar. 17, 2022.

- During this period the 341 MW also operated under the unit designation 341st Strategic Missile Wing and 341st Space Wing. I use 341 MW throughout this essay to avoid confusion. Troy A. Hallsell, “Building Malmstrom’s Minuteman Missile Fields in Central Montana, 1960–1963,” Air Power History 68:1 (Spring 2021): 5–16. On the Minuteman ICBM, see David W. Bath, Assured Destruction: Building the Ballistic Missile Culture of the U.S. Air Force (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2020); Heefner, The Missile Next Door; David K. Stumpf, Minuteman: A Technical History of the Missile that Defined American Nuclear Warfare (Fayetteville: Univ. of Arkansas Press, 2020). On the defense access roads program, see Darcel M. Collins and Darryl M. Hampton, “Defense Access Roads,” Public Roads 75:6 (May/Jun. 2012), 1–10.

- Jack A. Gannon, interview by Troy A. Hallsell, Nov. 20, 2020, Great Falls, Montana. Murray M. Moler, “Minuteman is Greatest in Magnitude Ever in Montana,” Great Falls Tribune, Sep. 22, 1960.

- James C. Bard, Sara A. Scott, and David C. Schwab, Base and Missile Cold War Survey: A Baseline Inventory of Cold War Material Culture at Malmstrom Air Force Base, Montana (Englewood, CO: CH2MHill, 1997), 12–13, 15, 24–25, 42. On the Air Force’s air refueling missions, see Richard K. Smith, Seventy-Five Years of Inflight Refueling: Highlights, 1923–1998 (Washington, DC: Air Force History and Museum Program, 1998); Ellery D. Wallwork et al., Air Refueling: Without Tankers, We Cannot... (Scott AFB: Office of History Air Mobility Command, 2009).

- The 29th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron was active at Malmstrom AFB from November 1953 to April 1968. Its pilots initially flew F-94C Starfires, and, later, F-89J Scorpions and F-101B Voodoos. Bard, Scott, and Schwab, Base and Missile Cold War Survey, 23, 26–28. On SAGE, see Kenneth Schaffel, The Emerging Shield: The Air Force and the Evolution of Continental Air Defense, 1945-1960 (Washington, DC: The Office of Air Force History, 1991), 197–209, 224–35

- Bard, Scott, and Schwab, Base and Missile Cold War Survey, 14, 28–39; Stumpf, Minuteman, 379–98.

- Matthew J. Ambrose, The Control Agenda: A History of Strategic Arms Limitation Talks (Ithaca, NY: Cornell Univ. Press, 2018), 9. On the role of nuclear weapons and arms control during the Cold War, see Ambrose, The Control Agenda; Richard A. Paulsen, The Role of US Nuclear Weapons in the Post-Cold War Era (Maxwell AFB: Air Univ. Press, 1994), 1–42.

- At that moment, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Ukraine wielded a combined 3,200 nuclear warheads, mostly atop ICBMs in their respective territories. See Graham Allison, “What Happened to the Soviet Superpower’s Nuclear Arsenal? Clues for the Nuclear Security Summit,” HKS Faculty Research Working Paper Series RWP12-038 (Aug. 2012), (source), accessed Aug. 17, 2022. Quoted in Paulsen, The Role of US Nuclear Weapons, 26. George H. W. Bush, “Address to the Nation on Reducing United States and Soviet Nuclear Weapons,” Sep. 27, 1991, (source), accessed Oct. 4, 2021. John C. Lonnquest and David F. Winkler, To Defend and Deter: The Legacy of the Cold War Missile Program (Rock Island: Defense Publishing Service, 1996), 131–33; Paulsen, The Role of US Nuclear Weapons, 22–42. By the time President Bush made this announcement, the Department of Defense already planned to deactivate the Minuteman II ICBM. See Stumpf, Minuteman, 399.

- Peter Johnson, “Malmstrom rolls with the changes,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 17, 1992; Peter Johnson, “Burns pushes for faster shift of missiles,” Great Falls Tribune, May 7, 1992. This author relied heavily on Tribune newspaper articles because they were the only sources available to tell this story. Montana’s elected representatives during this period either did not have an archival collection or their collection did not contain any information about their role during the Base Realignment and Closure process.

- Peter Johnson, “Way cleared for missiles,” Great Falls Tribune, Jun. 6, 1992; Peter Johnson, “Missiles on track for MAFB,” Great Falls Tribune, Jul. 29, 1992; Peter Johnson, “Good news for Malmstrom may be bad news for Wyoming,” Great Falls Tribune, Jul. 31, 1992.

- During this period the 564 MS also operated under the designation 564th Strategic Missile Squadron. I use 564 MS throughout this essay to avoid confusion. Stumpf, Minuteman, 399. On the Air Force’s deactivation of the Minuteman II ICBM at Ellsworth AFB, see Heefner, The Missile Next Door, 168–99.

- Bard, Scott, and Schwab, Base and Missile Cold War Survey, 15; “Next Decade: Business as usual on base,” Great Falls Tribune, Oct. 23, 1992; Stumpf, Minuteman, 405. The headworks comprised the top third of the launch facility. This included the launcher enclosure door, personnel access hatch, and launch equipment room. The wing’s conversion of the remaining 120 LFs began on Oct. 21, 1995, with the last MM III emplaced at LF B-08 on May 15, 1998. Peter Johnson, “Modernizing Mission,” Great Falls Tribune, Nov. 18, 1992.

- The Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission, Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission: 1995 Report to the President (Arlington, VA: Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission, 1995), ix.

- “Clinton picks Dixon to lead base closures,” Great Falls Tribune, Oct. 5, 1994; “Ellsworth backer on base closure panel,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 9, 1995. The 1995 BRAC committee consisted of Alton W. Cornella, a Rapid City, South Dakota, businessman who led a chamber of commerce task force to save Ellsworth AFB from closure; Rebecca G. Cox, vice president of Continental Airlines; retired fighter pilot Gen. James B. Davis; S. Lee Kling, chairman of the board of Kling, Rechter & Co., a merchant banking company; retired Rear Adm. Benjamin F. Montoya; Wendi L. Steele, former Senate liaison to the 1991 BRAC commission; and Michael P. W. Stone, a former U.S. Army secretary and DoD official.

- “All bases face sharp scrutiny in next round of closures,” Great Falls Tribune, Nov. 15, 1994.

- Peter Johnson, “Backers like Malmstrom’s chances,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 26, 1995.

- A squadron consisted of twelve aircraft and approximately 150 personnel. See James E. Larcombe, “Malmstrom, MANG nicked,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 1, 1994; “Montana’s delegation worried base may lose tanker function,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 26, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Base’s fate still not certain,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 26, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Backers like Malmstrom’s chances,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 26, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Base may lose tankers,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 1, 1995. A wing in the U.S. Air Force is a unit of command and typically consists of two or more groups. Depending on a wing’s mission it consists of an operations group, maintenance group, support group, and medical group. At the time of the 1995 BRAC, the 43rd Air Refueling Wing was the host unit, with 341 MW a tenant unit. This meant the Air Refueling Wing was responsible for Malmstrom AFB’s medical and support functions. However, after the Refueling Wing lost half of its aircraft, the Air Force reduced it to a group and transferred the medical and support functions to the 341 MW. “Montana’s delegation worried base may lose tanker function,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 26, 1995.

- Jefferson R. Cowie, Stayin’ Alive: The 1970s and the Last Days of the Working Class (New York: The New Press, 2012); Brian J. Leech, The City That Ate Itself: Butte, Montana and Its Expanding Berkeley Pit (Reno: Univ. of Nevada Press, 2018); Michael P. Malone, Montana: A Contemporary Profile (Helena: American & World Geographic Publishing, 1996), 61–63.

- Malone, Montana, 60. Michael P. Malone, Richard B. Roeder, and William L. Lang, Montana: A History of Two Centuries, rev. ed. (Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press, 1991), 323–28; Malone, Montana, 33–36, 60–67, 79–83, 98–108.

- Brenes, For Might and Right, 5–6; Peter Johnson, “All-out effort set to defend Malmstrom,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 27, 1995.

- Carol Bradley, “Base a third of local economy,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 28, 1995; Carol Bradley, “Great Falls folks love those flyers—for a lot of reasons,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 1, 1995; Jacquie Long, “Montana Refining will suffer,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 2, 1995; Peter Johnson, “All-out effort set to defend Malmstrom,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 27, 1995.

- Mark Downey, “Peace vigil draws few,” Great Falls Tribune, Apr. 20, 1992. Charles Chatfield, The American Peace Movement: Ideals and Activism (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1992), 146–64. On the history of nuclear energy, weapons, and anti-nuclear activism, see Paul Boyer, By the Bomb’s Early Light: American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age, rev. ed. (Chapel Hill: Univ. of North Carolina Press, 1994); Sarah Alisabeth Fox, Downwind: A People’s History of the Nuclear West (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 2014); Bruce Hevly and John M. Findlay, eds., The Atomic West (Seattle: Univ. of Washington Press, 1998); Valerie L. Kuletz, The Tainted Desert: Environmental Ruin in the American West (New York: Routledge, 1998); A. Constandina Titus, Bombs in the Backyard: Atomic Testing and American Politics, 2nd ed. (Reno: Univ. of Nevada Press, 2001); John Wills, Conservation Fallout: Nuclear Protest at Diablo Canyon (Reno: Univ. of Nevada Press, 2006). “341 Strategic Missile Wing Chronology: 1981” (Malmstrom: 341st Missile Wing History Office [341 MW/HO], 1982), 2; “341 Strategic Missile Wing Annual Chronology: January–December 1983” (Malmstrom: 341 MW/HO, 1984), 2; “341 Strategic Missile Wing Annual Chronology: September 1984–September 1986” (Malmstrom: 341 MW/HO, Jan. 1, 1987), 3; Mark Downey, “Peace vigil draws few,” Great Falls Tribune, Apr. 20, 1992.

- Heefner, The Missile Next Door, 155–56, 160–62.

- Peter Johnson and Rich Peterson, “Activists: Close air base, MANG,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 3, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Anti-nuclear activists want to say their piece Friday, too,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 26, 1995.

- Jacquie Long and Peter Johnson, “Hired gun to fight for base,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 22, 1995; Cheryl Phillips, “Racicot urges state to give to base fund,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 2, 1995; “House panel Oks $20,000 to help save base,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 4, 1995.

- Kirk Spitzer, “Military rating saved base,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 7, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Base may lose tankers,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 1, 1995; “Burns wants closure panel head to visit Malmstrom,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 3, 1995; Kirk Spitzer, “Hearings in Great Falls seem likely,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 4, 1995; “Air Force official to meet with area leaders on economic impact,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 4, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Base panel here on March 31,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 11, 1995.

- Peter Johnson, “Making a case for Malmstrom,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 26, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Malmstrom backers will push to keep airfield active,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 26, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Great Falls team maps hearing strategy,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 26, 1995.

- Peter Johnson, “Making a case for Malmstrom,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 26, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Malmstrom’s Moment,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 31, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Malmstrom on Parade,” Great Falls Tribune, Apr. 1, 1995; Richard Ecke, “Thousands present arms in waves to motorcade,” Great Falls Tribune, Apr. 1, 1995.

- Peter Johnson, “Great Falls team maps hearing strategy,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 26, 1995; “Public will be able to comment,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 26, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Malmstrom’s Moment,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 31, 1995.

- Peter Johnson, “Malmstrom on parade,” Great Falls Tribune, Apr. 1, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Montana’s top brass join forces to promote base, city and state,” Great Falls Tribune, Apr. 1, 1995.

- Peter Johnson, “Behind-the-scenes work on base is just beginning,” Great Falls Tribune, Apr. 2, 1995.

- Peter Johnson, “Base backers ready with prong two,” Great Falls Tribune, Apr. 24, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Delegation’s lobbying ‘turned the tide,” Great Falls Tribune, May 11, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Thumbs up for Malmstrom,” Great Falls Tribune, May 11, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Missiles staying, tankers gone,” Great Falls Tribune, Jun. 23, 1995.

- ICBM maintenance professionals determine alert rates by dividing the number of ICBMs ready for use by the total number in the force. Essentially, the more ICBMs that a unit has ready for use, the higher the alert rate. DBCRC, Defense Base Closure and Realignment Commission: 1995 Report to the President, 95–96, 101–3; Peter Johnson, “Thumbs up for Malmstrom,” Great Falls Tribune, May 11, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Missiles staying, tankers gone,” Great Falls Tribune, Jun. 23, 1995; “BRAC 95 and the Malmstrom AFB Runway,” Memorandum (Malmstrom: 341 MW/HO, Aug. 5, 1997). John Diamond, “Clinton Oks base closure plan,” Great Falls Tribune, Jul. 14, 1995.

- James E. Larcombe, “Reaction to base news: Sadness, not shock,” Great Falls Tribune, Jun. 24, 1995; Peter Johnson, “Missiles staying, tankers gone,” Great Falls Tribune, Jun. 23, 1995.

- Peter Johnson, “Search on for new missions here,” Great Falls Tribune, Jul. 14, 1995; Peter Johnson, “MAFB lands engineering unit,” Great Falls Tribune, Sep. 18, 1996.

- Peter Johnson, “MAFB lands shuttle tests,” Great Falls Tribune, Jul. 12, 1996; Richard Ecke, “X-33 expected to lead to lower-cost, frequent-flier shuttle,” Great Falls Tribune, Jul. 12, 1996; Peter Johnson, “New missions replace old at base,” Great Falls Tribune, Jan. 2, 1997. NASA cancelled the program in 2001. See “Historical Fact Sheet: X-33 Advanced Technology Demonstrator,” Apr. 12, 2008, (source), accessed Oct. 26, 2021. AFTC/PA, “November 14, 1997: X-33 Launch Pad Construction Began,” Nov. 14, 2020, (source), accessed Oct. 26, 2021.

- Peter Johnson and James E. Larcombe, “Missile cuts in plan,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 4, 2006; Peter Johnson, “Malmstrom cuts likely,” Great Falls Tribune, Feb. 10, 2006; Peter Johnson, “Leaders working together to save missiles,” Great Falls Tribune, Jan. 26, 2007; Peter Johnson, “Rehberg, Tester introducing move to save missiles,” Great Falls Tribune, Jan. 27, 2007; Jo Dee Black, “Delegation to fight for missiles,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 29, 2007; Peter Johnson, “Leaders working together to save missiles,” Great Falls Tribune, Jan. 26, 2007.

- Peter Johnson, “Draft assessment: Missile removal wouldn’t adversely affect environment,” Great Falls Tribune, Apr. 28, 2007; Peter Johnson, “Missile dismantled, warhead removed,” Great Falls Tribune, Jul. 14, 2007; Zachary Franz, “Airmen remove final missiles,” Great Falls Tribune, Aug. 1, 2008; Peter Johnson, “Era ends for 564th Missile Squadron,” Great Falls Tribune, Aug. 16, 2008; “New START Treaty,” Sep. 23, 2021, (source), accessed Sep. 28, 2021; Peter Johnson, “Senate Oks New START nuclear arms treaty,” Great Falls Tribune, Dec. 23, 2010; David Murray, “Air Force shares silo removal plans,” Great Falls Tribune, Dec. 6, 2011; “History of the 341st Missile Wing: 1 January 2014–31 December 2014” (Malmstrom: 341 MW/HO, 2015), 108. John A. Turner, “Demolition of final ‘Deuce’ squadron missile launcher is a New START milestone,” Aug. 6, 2014, (source), accessed Oct. 4, 2021.

- Phil Drake, “Gianforte says fix Malmstrom runway rather than build elsewhere,” Great Falls Tribune, Jul. 12, 2019. In fiscal year 2021, 341 MW estimated that Malmstrom had a direct economic impact of $314,541,581 and produced an estimated $69,670,864 in indirect economic activity across Cascade, Chouteau, and Teton Counties. See “Commander’s Data Card: Fiscal Year 2021,” (source), accessed Aug. 18, 2022.

- Montana witnessed an estimated $5.15 billion in nonresident traveler expenditures in 2021. See Kara Grau, “2021 Nonresident Visitation, Expenditures & Economic Impact Estimates,” Institute for Tourism and Recreation Research Publications, no. 430 (Apr. 2022), 2, (source), accessed Sep. 14, 2022. “Great Falls: Montana’s Basecamp,” (source), accessed Sep. 14, 2022; Grau, “2021 Nonresident Visitation, Expenditures & Economic Impact Estimates,” 13; Austa Somvichian-Clausen, “The Great American Outdoors Act passes with bipartisan support,” The Hill, Jul. 24, 2020, (source), accessed Aug. 18, 2022; Jenn Rowell, “Touro Breaks Ground on Proposed Great Falls Medical School,” The Electric, Oct. 6, 2021, (source), accessed Aug. 18, 2022.

- W. J. Hennigan, “Inside the $100 Billion Mission to Modernize America’s Aging Nuclear Missiles,” Time, Sep. 13, 2022, (source), accessed Sep. 14, 2022. See also Patty-Jane Geller, “China’s Nuclear Expansion and Its Implications for U.S. Strategy and Security,” Heritage Foundation, Sep. 14, 2022, (source), accessed Sep. 14, 2022; Michael E. O’Hanlon, “Strengthening the US and NATO defense postures in Europe after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine,” The Talbot Papers on the Implications of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine, Jun. 21, 2022, (source), accessed Sep. 14, 2022. Hennigan, “Inside the $100 Billion Mission.” James E. Larcombe, “Malmstrom, MANG nicked,” Great Falls Tribune, Mar. 1, 1994.

|