|

|

|

|

|

«Oscar-Zero»

© Oscar-Zero. RRMMSHS», 2012.

Our address: en@rvsn.info |

|

See also: Project Long Life II For a video of this blog : October 19, 1966, was another beautiful day on the northern prairie. The day had started with temperatures in the low 20s but by noon the temp was climbing into the 40s. The approximately 150 people that were gathered about 6 miles south of Michigan, North Dakota were excited to witness the launch of a Minuteman II from the H-24 (“Hotel-24”) launch facility (one of 150 such facilities that had been recently constructed in eastern North Dakota). The launch, part of the Air Force’s “Project Long Life” promised to be quite the spectacle for the high-ranking Air Force Generals, local VIPs, countless reporters, and numerous local citizens. This was to be the second launch in “Long Life”–the first had occurred over 1 year ago near Newell, South Dakota when the 44th Strategic Missile Wing launched one of their missiles. Granted, the specially modified test missile was altered to ensure the missile was powered for no longer than 7 seconds and would impact within a mile of its launch point, it still promised to be an incredibly exciting sight for those gathered on the prairie. This was the Air Force’s second attempt at this launch–the original attempt was scheduled for Oct 12 but was postponed several days when the Air Force had discovered a malfunction in the special test equipment on the missile. However, since the malfunction was found days in advance, there was little excitement or concern over the postponement. The gathered crowd on the 19th also included five farm families that the Air Force had forced to evacuate their homes. Although the Air Force was very confident that it “knew” where the missile would come down, it nonetheless wanted to ensure nobody was harmed. The Hamre, Yoney, Danda, Senger, and Anderson families all waited patiently along with the others for the eventual launch. Donald Hamre and his family not only evacuated themselves but also their herd of cattle that was in a pasture that overlapped the expected impact area. As the time to launch grew closer the anticipation mounted. Then the Launch Director, Lt Col James Simmons and the Task Force Commander, Col Joe Schonka announced that the launch would be delayed. The crowd was disappointed and confused. The Air Force went into action and a helicopter hurried a replacement for a failed component from Grand Forks Air Force Base to the launch site. However, the leaders felt that hurrying the repair was just too risky and the launch was indefinitely postponed. Suddenly the gathered folks probably felt a bit more of a chill in the 40 degree afternoon. Of course, everybody wanted to know one thing, “What went wrong?” The Air Force explained that an electronic part that isolated the test missile from armed missiles in the same area had malfunctioned and they tried to reassure everybody that if it had been a wartime scenario, they could have gone through with the launch but it just wasn’t worth the risk in this test environment. So, the Federal Aviation Administration lifted the 10 mile, 10,000 foot no-fly-zone surrounding the launch site, the road blocks around the two mile perimeter were removed, and the farm families were allowed to return to their homes. A few days later, on October 26, the Grand Forks Herald reported that the next attempt would take place on October 28. The anticipation began to build once again. On the morning of the 28th, the no-fly-zone went into place, the road blocks cordoned off a two mile area, and the farm families were forced to evacuate their homes. The nearby people of Michigan and Petersburg, North Dakota waited in what must have been dubious anticipation. The crowds of dignitaries, locals, and journalists came again to the remote missile silo on the prairie. This time, they were joined by protestors who had just received word of the launch the night before. The protestors were led by Reverend Robert L. Branconnier, one of two Roman Catholic priests from the University of North Dakota. This man of the cloth felt it was his “responsibility as a priest to be a prophetic voice and warn of danger.” He and his fellow protestors were there to raise questions about the morality of these nuclear weapons that indiscriminately targeted large population centers.

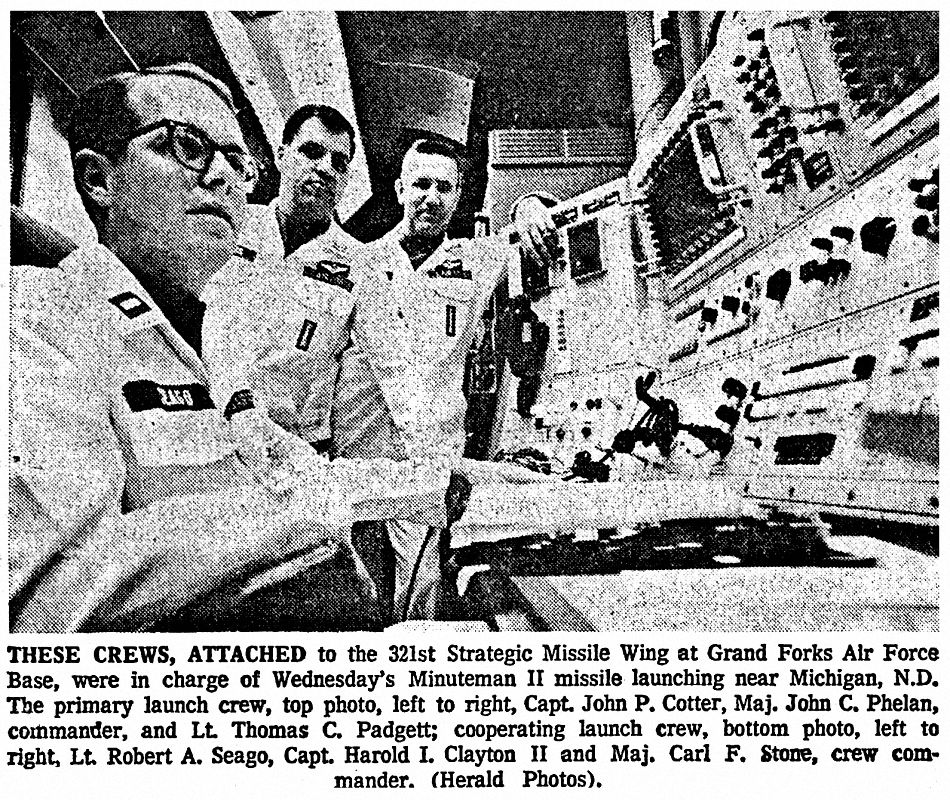

As the protestors picketed and the on-lookers waited, the launch progressed. Finally the time came when the below ground launch crews, one crew led by Major John J. Phelan and the other led by Major Carl E. Stone, began their launch procedures. Simultaneously, the crews turned their launch keys, but the missile just sat quietly in its silo and refused to launch. Disillusionment rapidly spread throughout the gathered crowd. This was the third scheduled attempt to launch, and the third failure. The Air Force confirmed that the crews followed through with their launch procedures, but that the first stage of the rocket simply failed to ignite. As cynicism spread throughout the crowd, someone asked, “When will they try it again?” One person answered, “How about April 1!” Another answered, “How about October 31–tricks and treats!” While another chimed in, “Maybe they should have called it Project Long Wait” After just witnessing a massive two-year construction project that emplaced 150 nuclear missiles in North Dakota soil–missiles that despite other successes, now appeared extremely unreliable–the local confidence in the wisdom of the Air Force must have reached an all-time low. As for Rev Branconnier and his protesters, they were relieved to witness the failure. Branconnier hoped that this “would spark a discussion on the campus,” where he felt there was “an increasing apathy toward the use of these weapons.” He went on to wonder “. . .how much this cost. How many University students could have been given loans with this money?” Over a month later, on December 7, during ceremonies when the Strategic Air Command accepted the fully operational 321st Strategic Missile Wing the Air Force announced that they had not given up on “Project Long Life” and that the test would occur sometime in 1967. The Air Force proclaimed that despite the previous failures, they had complete confidence in the Minuteman II. Then, in February, the Secretary of the Air Force sent a letter to North Dakota Senator Milton Young to ensure him of his confidence in the Minuteman. Brown wrote, “an analysis of the facts involved in these attempts does not reduce our confidence in Minuteman II reliability.”

In the summer of 1967 the Air Force moved forward with their plans to launch a test missile from the Grand Forks missile field but they had renamed the project. Project Long Life was now referred to as Project Giant Boost. Perhaps the Air Force was hoping for a “Giant Boost” to the reputation of the Minuteman II missile. The Air Force scheduled the test launch for August 14–anticipation and hopes were high. When the day arrived, and everything was in place, the test failed…again. According to the Office of Air Force History, “When the launch aborted, the Air Force rushed a 7-second missile to Vandenberg Air Force Base, where it was successfully launched.” Secretary Brown believed that that successful test must have restored public confidence in the Minuteman; he certainly had confidence in the missile. Brown may have been satisfied, but the confidence of many of the stoic, practical farmers of the Northern Plains, who tend to follow a “show me and then I’ll believe you” philosophy probably never returned after the 4 scheduled, and 4 failed attempts to launch the Minuteman from their backyard. As it turned out, after that first successful launch from an operational silo in South Dakota in March of 1965, that first test of Project Long Life, the Air Force never again launched an intercontinental ballistic missile from an operational site. The failure of Project Long Life and Giant Boost scarred the reputation of the Minuteman. However, if all you knew of Minuteman test launches was those failures, your knowledge would be very incomplete. Test launches of Minuteman missiles have occurred over 100 times in its 50 year history. Today, the Air Force still conducts numerous annual test launches. These tests are typically very successful. A very significant difference between Long Life and the test launches that have occurred since then (and still occur today) is that the Long Life tests were to take place at operational missile silos and all other tests occur from Vandenberg Air Force Base (on the central coast of California). Photos in video and this blog courtesy of: ► State Historical Society of North Dakota ► Association of Air Force Missileers ► Grand Forks Herald ► John Whiteside graciously donated copies of his personal scrapbook that he kept while a Targeting and Alignment Officer at Grand Forks Air Force Base in the mid-1960s. His scrapbook provided insight into the importance of Project Long Life in the early years of the 321st Strategic Missile Wing This project was provoked by the numerous times the staff at the Ronald Reagan Minuteman Missile State Historic Site have been asked “How did they test the missiles?” While the guides often share this story they also explain the numerous, and successful, tests that the Minuteman has experienced at Vandenberg Air Force Base. We’ve met more than our fair share of North Dakotans that remember project Long Life II and who still wonder if the Minuteman of Grand Forks ever would’ve launched if called upon…thankfully we never had to find out…

|