|

|

|

|

|

Charlie Simpson,

© «AAFM», 2001-2002.

Our address: en@rvsn.info |

|

See also: The ICBM Force in the Early 1960s - Part I «AAFM», December, 2001.

AAFM members have been involved with intercontinental ballistic missiles for more than forty years - the first Atlas D was on alert at Vandenberg on 31 October 1959. By that time, missileers had already been operating Matador, Mace, Snark, Thor and Jupiter. The years 1961 and 1962 were especially busy years for missileers as the ICBM force quickly grew to six Titan I squadrons and twelve Atlas squadrons, in addition to the Vandenberg units. The same period also marked the beginning of activity in both Titan II and Minuteman I - our ICBM force was expanding rapidly, and we were in the middle of the Cold War, Throughout the next year, the AAFM Newsletter will feature several articles about the missile force in the early 1960s. The September issue and the October AAFM National Meeting in Santa Maria will focus on an especially historic time - the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. The ICBM force came of age in that crisis - many of us were as close to war as we ever were throughout our years as missileers. Our new Atlas and Titan I missiles were all in the highest state of readiness that we had short of loading lox and launching, and the first Minuteman I missiles were rushed to alert status during the October crisis. The articles beginning on page five are the first in this special series about the early days of the ICBM force. Others will follow throughout this year - you are encouraged to send your stories and personal experiences to us to become part of this series. Getting Started in Titan I - 1961

Forty years ago, many of us were beginning our careers - or our one-time experience - in missiles. We were being trained as intercontinental ballistic missile operators or maintainers, or were becoming involved in some other aspect of the rapidly developing ICBM force. We werent the first - we had been preceded by missileers in Matador, Mace, BOMARC Snark, Navaho and the early airlaunched missiles, along with those involved early in the life of the AF in designing, testing and developing other systems. We werent even the first troops to be involved with ballistic missiles - Jupiter was in Italy and Turkey, the Thor was deployed in England and the Atlas D and E units had been activated and manned beginning with the first units in 1958, But starting in 1960 with the Titan I wing at Lowry and followed shortly by the other Titan I and the six Atlas F units, we were in the middle of a gigantic buildup of the US nuclear deterrent missile force. A lot of us trained at Sheppard AFB, Texas, with some classes being taught twenty four hours a day. We were training in every specialty required to maintain, support and operate these new systems, and we were learning a whole lot about a lot of related subjects. Many of us had already completed training and were in our new units, busy with the process of setting up shops and offices, or taking part in the acceptance process as contractors turned the new missile sites over to the Air Force. Some of us were busy, but others were just waiting. We had new jobs but we had no system to practice what we had just learned at Sheppard. I began training at Sheppard in early October, 1961. I had entered the AF a little less than two years before as an aircraft maintenance officer, and had volunteered for the new Atlas and Titan missile systems when the AF began asking for volunteers late in 1960. My class at Sheppard (the Launch Control Officer Course or the basic missile course) included about 25 officers, mostly lieutenants and captains, with a few majors and lieutenant colonels, who were heading for one of the new Atlas F or Titan I units. A large number of members of my class was headed a short way up the road to Altus AFB, Oklahoma, to the 577SMS, which had been activated three months before. My class also had two students that were destined to an even newer weapon system - they were some of the very first selected for Minuteman I duty at Vandenberg. Most of the class were heading for duty as missile crew members, but a few of us, me included, were heading for missile maintenance, and one or two would end up in other missilerelated jobs.

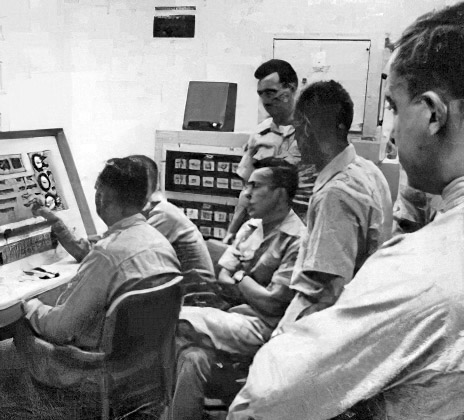

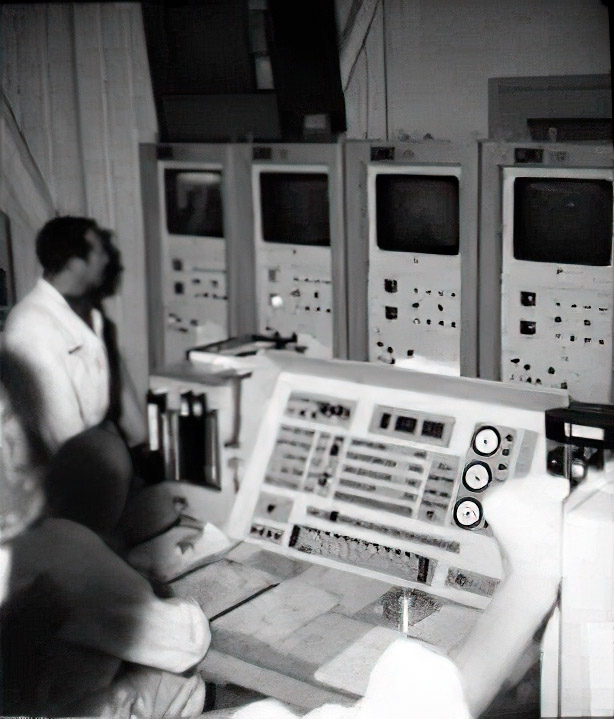

The basic missile course was in a state of change - we were supposed to be in the class until after Christmas - but early in our training, some changes in the curriculum shortened our course so that it ended right before Christmas. I was in the morning class - 0600-1200 - and there were at least three classes in progress - even four during part of my stay at Sheppard. The 0001-0600 class had to be a real joy (I learned it was four years later in Minuteman II training at Vandenberg, when, as the junior member of my class, I got to spend three weeks in the trainer portion on that schedule- I never did figure when the best time to sleep was). We studied USAF organization and policy, AF regulations, mathematics, physics and electronics. The electronics phase was the longest - almost four weeks, which included a lot of lab time building breadboard circuits and learning about computers. We ended the basic course with a detailed study of the Thor system - we learned all about the missile airframe, propulsion, guidance, launch site facilities (even the sewage and water systems) and everything else about Thor. We were told that this phase of training would prepare us for all the basics so we would have a better understanding of the specifics of Atlas F or Titan I - or whatever other system we ended up in. The Atlas folks in my class only had a short break before they started the Atlas F course, but I was told that the next Titan course wouldnt start until after Christmas, so I had a long vacation in Wichita Falls. We werent allowed to leave the area unless we signed out on leave - I had such a small leave balance, I had to stay in the area. The Titan I course was more intense and more specific. My class was mostly officers heading for Mountain Home (569SMS) with me, and most were headed for crew duty. A couple of us would become missile maintenance officers in the squadron - I suppose my vast experience in aircraft maintenance made me well qualified to continue as a maintainer. We spent a lot of time with colored pencils, tracing electrical circuits, liquid oxygen flow, the missile elevator hydraulic system and the power house systems. We learned all about the radio guidance system, hand-off, backup antennae and every other aspect of the complex Titan I system. We spent the last few days sitting at either cardboard mockup consoles or one of the rudimentary training consoles - not quite as exotic as current missile procedures trainers.

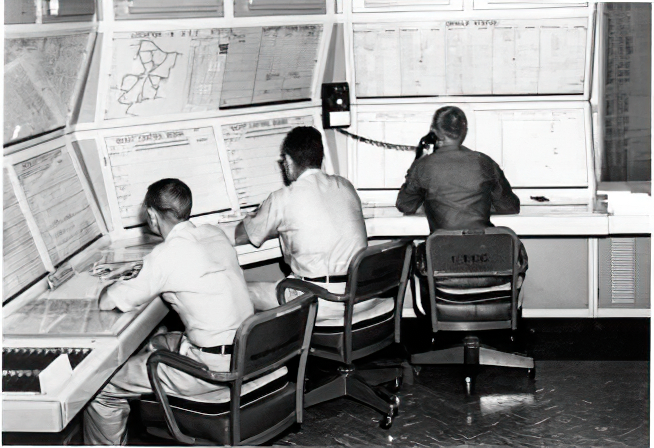

I reported for duty in the 569SMS in mid-February, and met my new boss, LtCol Loyd Jensen, who had come from a B-47 maintenance job in Texas, and the DCM, LtCol G. B. Jannot (those who were allowed to address him by his first name called him Jan or just Jannot - I learned very early never to use his full first name in a signature block on a letter or message.) He had come to Mountain Home when the base first reopened with B-29s, and had spent several years in B-47 maintenance before moving to the new Titan I squadron. I was told that I was the new Job Control Officer, and Col Jensen took me into the new job control center - a large empty room next door to the DCMs office. When I say empty, I mean empty - no chairs, no desks, no phones - but we did have a bunch of boxes that said they contained the standard 15AF Job Control Console. I also met my new troops - most had come from Matador or Mace in Germany or Okinawa. My NCOIC was TSgt Robbie Robinson - someone that a new first lieutenant learned a lot from in the coming months, and still a good friend - now a retired SMSgt living in Idaho. The rest or the initial Job Control staff consisted of a couple of TSgts, some SSgts, like LeRoy Hudson, and a couple of Airmen First Class - back when an A1C had three stripes and there were no Sergeants. Next door to us was the Plans and Scheduling office, with NCOs Bob Nelson, Herbie Vice and Roy Hogstrom also hard at work trying to figure out what to do with their empty room. Between our first gathering in February and mid-June, we built our office complex. For Job Control, it meant constructing a number of large status boards to keep track of missile status, to record exercise results and to display equipment location and status. We decided that we werent particularly found of the standard 15AF Job Control Console, which looked like it was made from excess high school gym lockers, so we only used the bottom half of it, and stored the top sections, which were designed to be the status boards. Col Jensen turned us all into woodworkers, to fulfill his idea of a wood-paneled Job Control room - it looked superb when we finished. Next door, the P&S folks were busy designing planning boards and work order file systems - we all worked together on all of it, since we had no other duties. A bunch of us found a good way to keep in shape - and injure each other. We started playing water polo - but not the Olympic variety. Since some of the players were better waders than swimmers, we played our version in the shallow half of the indoor base pool. We called it water polo, but it was basically tackle football in shoulder deep water. We stayed in shape - but we had a few bloody noses, black eyes and sprained muscles. This sport came to an end when the pace of work rapidly accelerated as the first missile came near to being ours. During this same time, the ops crew members (there were four in Titan I - the missile launch officer, the guidance officer, the ballistic missile analyst technician ant the missile maintenance technician) headed for Vandenberg for operational readiness training. Those of us in maintenance also went to Vandenberg, but our training was anything but a structured class. As a new missile maintenance officer, I spent a week ( shortened by one day because President Kennedy came to visit and they wanted us TDY folks out of the way) with the 395SMS Titan I Job Control people. Most of the four days were spent sitting, watching how they did things, and one day was spent touring the Vandenberg Titan I site. The Vandeberg site was somewhat like ours at Mountain Home - except for the ground level, concrete block control centers (two of them), the spiral stairway in the silos and the lack of a power house. On return to Mountain Home, after a stop in Seattle for the opening of the 1962 Worlds Fair, the pace picked up. I spent many days on site involved in site acceptance tasks - following a contractor around with a checklist to see if everything that was supposed to be there really was. We then watched the acceptance dual propellant loading of all three missiles - first at C site - the only time all three missiles on a site were loaded with both RP-1 and Lox and raised topside at the same time. Following that test, the first missile belonged to the AF and the men (and very few women) in the 569SMS. We started twenty four hour operation in Job Control shortly before the first missile was ours, and the hours got long for some of us. Most of my folks worked twelve hour shifts, seven days a week, until we had more manning, but Robbie and I worked a single shift each day - and it was usually about nineteen or twenty hours long. If you read the article in the September 2001 issue called The First V1, you will get some idea what a call to the SAC or 15AF command post was like - and we called every time a missile changed alert status - which, by their definition, happened several times a day. Every time we lowered a work platform or performed any kind of routine inspection or liquid/gas servicing, we had to call the missile off alert by telephone and hard copy message. It was not unusual to have three or four people running message forms to the command post at once, because the 9th Bomb Wing command post decided they couldnt take a V-1 report by telephone. That problem ended when, on the first visit by the SAC IG, I was asked why there was so much traffic in and out of job control through the electrically controlled door - the colonel who was team chief picked up the direct phone to the command post, asked for the senior controller and told him that effective immediately, V-1 reports would be done by phone. Hooray for the SAC IG on that one.

Unfortunately, some wise leader at 15AF decided we should have a separate alert tracking system for them - we had to submit an alert summary message at midnight local seven days a week. Since the message had to be released by at least the Maintenance Control Officer or the DCM, it meant that every night at midnight, the Job Control Officer (me) was in Col Jannots office at about 2345 getting his final approval on the message form. Col Jannot had a unique reading technique - he would use a pen to guide his eyes along each line of the message - and of course the pen would leave an underline under each word. Naturally, the comm center would not accept a message form with pen underlines - so each night, after the first reading, we got to retype the message and assure Jannot that what he was about to sign was exactly the same as the copy he had just underlined. This wonderful Midnight Duty lasted for several months, until the IG convinced 15AF that a single alert status report (the V-1) would do the job by itself. The people at 15AF decided early that we needed a team to go to each Titan I unit and make sure we each did things the best - that means the same - way. The team was made up of officers and NCOs from all the units - my boss, who was then Major Oscar Hermann, was one of the Mountain Home team members. That bode well for us in most areas - but we were in real trouble in one. The team chief (some of you may remember Col Curly Milner from Larson) couldnt understand why our Standard 15AF Job Control Console had no top half - and we couldnt convince him that our idea of big boards on the wall was better. It seems that all the other units had used the whole console - so we did, too. So now, we were up and running, we were standardized, and we were very, very busy. All of us in the 569SMS quickly learned that keeping nine missiles - or any number less than that - on alert was a full time, twenty four hour a day job - we all put in countless hours operating, checking, inspecting, exercising and maintaining a very complex missile system. Exercises were the biggest single part of the job, and of course, we exercised at least every six months during a SAC ORI - trying to pass like all the other Atlas and Titan I units. This pace continued throughout the short life of the wet missiles - the quietest time may have been the weeks we spent on the edge of nuclear war during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October and into November of 1962 - but that is another story. The Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 - My Contribution The Place: Sheppard Air Force Base, Texas - The Air Training Command location of the Ballistic Missile School, in the barren, flat, treeless lands of north Texas. As all the many Missile school graduates will well remember; a place which is well away from any major population center and a long, long way from Cuba. The Missile School offered courses in the operations and maintenance of Atlas, Titan and Thor systems. I was a 2Lt, an instructor in the Titan I Branch, Radio Guidance Course. There were over 15,000 Tech School students attending the many officer and enlisted courses. Training occurred on a three shift, twenty four hour training day. The typical student was an 18 year old first termer, who had just graduated from the rigors of Lackland - and he was just beginning to express himself. We also had a resident SAC squadron. To aid in managing the enlisted students, all junior grade permanent party officers were assigned, as an additional duty, to one of the Student Squadrons. We were to counsel the airman and whatever other tasks were assigned by the overworked Squadron Commander. And then there was the Cuban missile crisis; clearly a nationally important event. We were military, we should be doing something!! Even if it was not obvious just how a Tech School, located many miles from the scene of action could contribute. At meetings to which the lowly were not invited to participate, the powers to be decided that what the School would do would be to organize and deploy a Base Defense Force. This force, apparently - as I was not fully read into the objectives of the concept - would defend the base in case of an attack by Cubans or their sympathizers. Now the base defense force would be entirely separate from the Security Police. They would remain clearly focused on base police matters, traffic management, and patrolling the SAC area and the fuel depot. The Base Defense Force would consist of students squads, led by an officer from the Student Squadron - one of which was me. Sheppard is a very large base, covering many hundreds of acres, and as there were no vehicles assigned to the Base Defense Force, it became immediately clear that the Force could not defend the perimeter of the base. The concept was that a trained squad of students would deploy - when needed, on one of the roads entering the base; a road which was not too far from where the students were barracked. The plan was - when alerted by siren signal, all the students squads would deploy from their barracks, double time to the rally place and form a cordon across the road to be defended. Some time later, a truck would arrive from the armory and the needed weapons, vests and helmets, would be issued - No ammunition was ever issued. We would then man our duty station until relieved. We rehearsed and drilled until we got it right - in the manner of military forces from time immemorial. As I was the Officer In Charge of the detail, I would be advised in advance of the time for the drill and would be at the rally point first, waiting for my men to form the cordon, watching for the armory truck, overseeing the careful unloading of the weapons and gear, take station, and then when the alert was over seeing that the supplies were put back onto the truck and dismiss the squad. I was very proud of my men. They were doing an excellent job in spite of Sheppard - I may have forgotten to mention that Sheppard most of the time is windy, hot and dusty - so hot that the asphalt gets soft. The rest of the time it is windy and cold. Things were going very well for the Base Defense Force. First stage was well along and so a more realistic exercise was thought up. To test the training, an idea emerged to do the whole deployment exercise but this time the officers assigned to the squads would not be able to interact with their men. The men should be able to conduct the task without their Lt being around. I was able to be present, but was not to speak to, or signal, the men. There would be a NCO from Headquarters, standing by with a clip board, making notes on the success of the exercise. The day came, the siren sounded, the men fell out of their barracks and double timed to the road - so far, so good. They formed a nice cordon line across the road, standing At Ease, facing the entry gate. Then, right on schedule, came the truck from the Armory; parked behind the line of men. The Armory Sergeant opened the tail gate and first he unloaded the weapons. The procedure was, one man at a time would leave the cordon, come up to the back of the truck, be issued a rifle and then return to his station on the cordon. Following the weapons the vests were issued, following a similar procedure, one man at a time. And then the helmets were to be issued. Now - someone at the Armory had got word that this exercise would be witnessed by a watcher from HQ (the Sgt with a clip board) and so someone had decided that some spiffing up would be warranted. A good hearted soul decided to paint the helmets - and they were stacked before the paint had completely dried. There in the back of the truck is standing the Armory Sergeant. He picks up a stack of helmets, he tries to take off the top one and give it the man standing in the road - No Luck. He tries again, this time with vigor - No Luck. The man on the ground gets into the truck in order to help. Now there are two men working on the helmet stack - No Luck. The other men, noticing that the activity around the truck is detrimentally delaying the whole process decide to assist. One man leaves the cordon in order to be of assistance, leaving his rifle laying on the ground. Several more men decide to assist. In no time, all the men are at the back of the truck, their weapons are not with them. After much tooing and froing and throwing of the stacked helmets from the truck onto the ground, several of the helmets are broken free and a few of the men obtain the necessary head gear, they return to the cordon. Unfortunately for the squad, the watcher concluded the exercise and said we had failed. The crisis passed, the men were not admonished - at least not by me; I was able to overcome this blemish and go on to a great career in the Air Force.

The Air Force in 1962 «AAFM», Mars 2002. Newsletter of «Association of Air Force Missileers»

This issue of the AAFM newsletter is the second in our series about missiles in the 1960s, a critical time in the development of both ICBMs and the continuation of development of tactical missiles and airlaunched systems. The September issue will contine this series, featuring more articles and stories about the early days in our business. In 1962, the Strategic Air Command was a large, dynamic organization. The history of SAC published by the SAC Office of History summarizes the strength of the command as having 282,723 members, including 38,542 officers, 217,650 airmen and 26,531 civilians. SAC had 2,759 tactical aircraft (639 B-52, 880 B-47, 105 EB-47, 41 RB-47, 76 B-58, 515 KC-135 and 503 KC-97), 59 aircraft wings, 57 Tanker squadrons and four EB-47L squadrons. The SAC missile force consisted of 142 Atlas, 62 Titan I, 20 Minuteman, 547 Hound Dog and 436 Quail, with 13 Atlas squadrons, six Titan I squadrons, six Titan II squadrons (with no missiles yet assigned) and eight Minuteman squadrons (only one with missiles assigned). SAC had 43 bases in the US and 14 overseas. General Curtis LeMay was the AF Chief of Staff, and Gen Thomas Power was CINCSAC. The Air Force had more than 887,000 military members, 139 stateside and 109 overseas bases. The Thor was still deployed in England and the Jupiter in Italy and Turkey. Air Defense Command had BOMARC sites, mostly in the northeast US, and the Mace was operational in Germany and the Pacific. Missileers involved with airlaunched systems were working with Genie, Falcon, Sidewinder and Bullpup in addition to the Hound Dog and Quail mentioned abouve. The Skybolt was still alive and being tested for deployment with SAC and the Royal Air Force. The inventory of aircraft was a mix of older propellor driien aircraft like the KB-50, B-26, C-47, KC- 97, C-119 and others to new jet aircraft like the B-58, F- 106 and F-4, and the RS-70 was being tested. John Glenn made the first US orbital flight, and the AF was increasingly becoming involved in space activities. A review of the AF Magazine “Highlights of the Year” for 1962 includes seven pages of specific events that included many Atlas, Titan and Minuteman launches from Vandenberg, space launches from both coasts. On March 23, 1962, President Kennedy watched an Atlas D launch from Vandenberg. 1962 was a very busy year for all of us who call ourselves missileers.

Missileers and the Cuban Missile Crisis «AAFM», September 2002. Newsletter of «Association of Air Force Missileers»

All of us who were missileers in 1962 were very busy - many of us had recently reported to the newly activated Atlas F and Titan I squadrons. We were working long hours in maintenance or pulling lots of alerts trying to get our new liquid-fueled systems up to speed. Others had already spent a year or more with the Atlas D and E, or were in Europe and the Pacific working on the Matador and the new Mace. Others were in England, Italy or Turkey working with the locals on Thor and Jupiter IRBMs. Many were in training preparing to head for their first assignment as missileers, especially since Minuteman and Titan II were coming fast. Some were in place at the first Titan II and Minuteman wings to activate. Others were working with BOMARC or with a variety of airlaunched systems. And many weren’t missileers yet, still working in aircraft maintenance, as pilots or navigators or in other Air Force specialties. The SAC ICBM force had grown rapidly in early 1962 - at the end of 1961, SAC had 30 Atlas D, 32 Atlas E, one Titan I, 230 Hound Dogs and 397 Quail. A year later, we had 30 Atlas D, 32 Atlas E, 80 Atlas F, 62 Titan I, 20 Minuteman, 547 Hound Dog and 436 Quail. All of the Atlas F and Titan Is had become SAC assets in the few months before October. I reported to the 569SMS at Mountain Home AFB, Idaho, in February, after spending almost five months in training at Sheppard. My first three months were anything but busy - we had no missiles, no sites and only empty rooms in the squadron. I was the Job Control Officer - with no Job Control. By May, we were starting to accept our new sites missiles. By October, we failed a practice ORI (like every other unit) and run a lot of PLXs (propellant loading exercises). In maintenance, we were working seven days a week, sometimes 20 hours a day, and the ops crews were on alert ten to 13 alerts each month. In late summer, SAC decided that all units had to find out how good our new systems were - we were directed to run ten consecutive PLXs on each missile, with the last two successful.

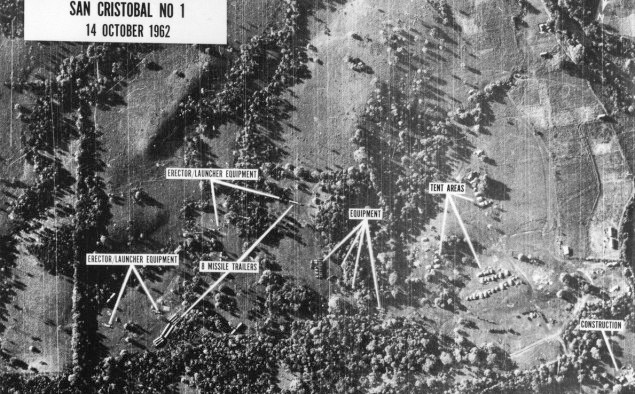

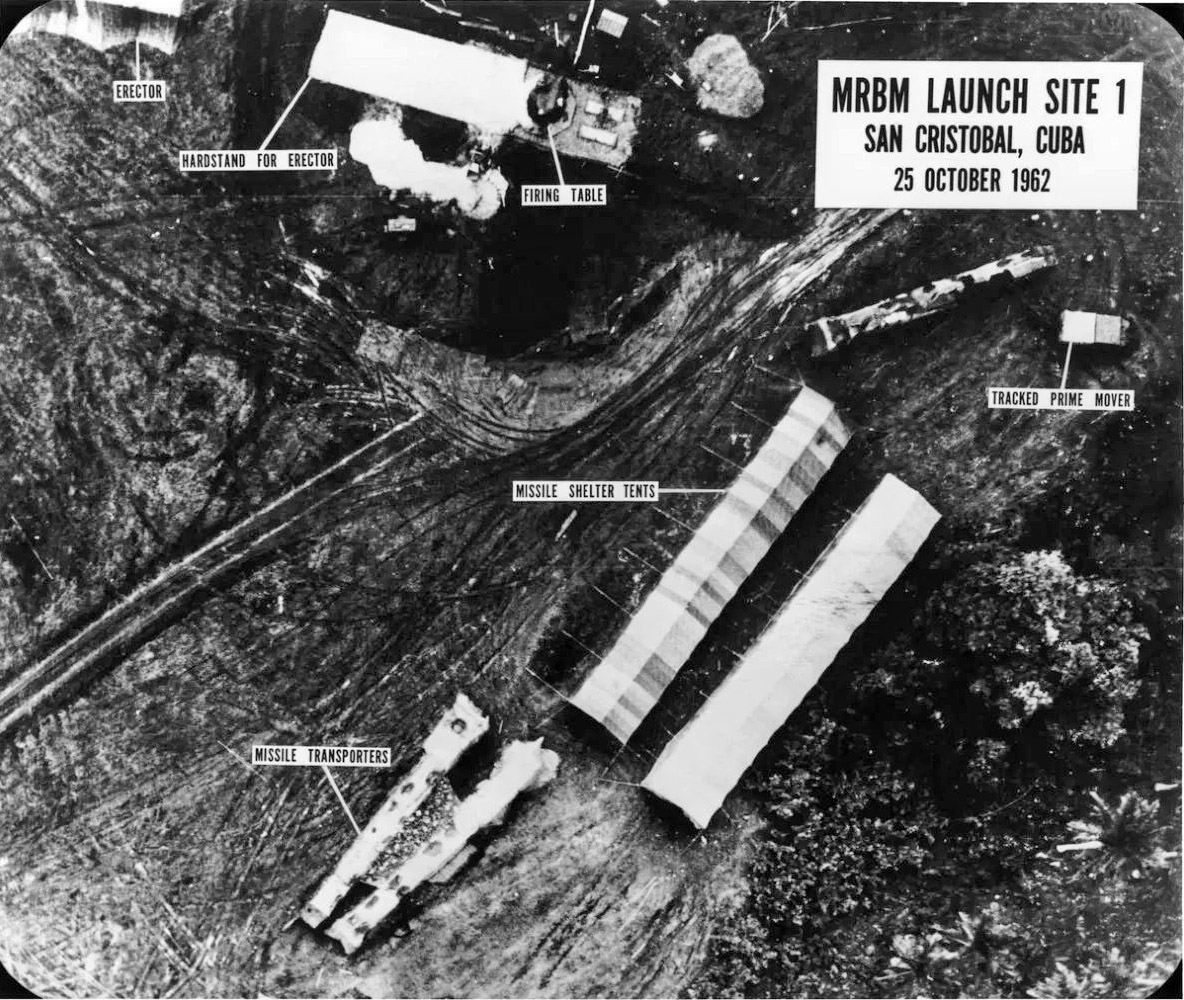

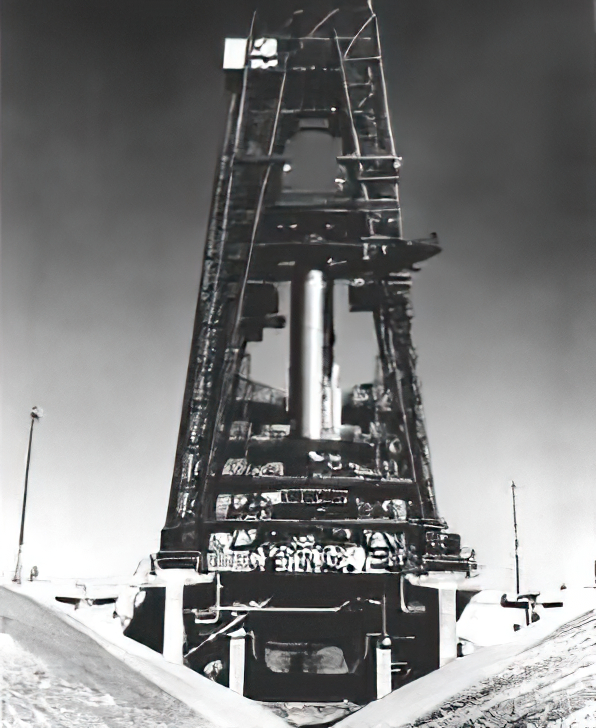

A PLX was a long and complex procedure. The RP-1 was removed, the ordnance was removed or disconnected and television cameras placed in the silo, equipment terminal and topside to monitor the exercise. We loaded lox, nitrogen and helium. The loading took about eight to ten minutes, and then the missile was raised on the silo elevator to the launch position. Once up and locked, the crew only had a short time to complete the launch sequence - in our PLXs, the guidance system locked on and the flight was simulated with the missile still sitting on the launcher. Then came the hard part - the missile was returned to the silo (or at least it was supposed to - sometimes we had to leave a “popsickle” topside for a couple of days to boil off) and the lox was offloaded back into the lox storage tank. It took a couple of days to prepare for the next exercise - longer if something failed, which happened over half the time. We could only prepare and exercise one silo at a time - the only time we exercised all three was during the final acceptance from Martin. On Sunday, 14 October, a U-2 flown by Maj Richard Heyser captured images in western Cuba that Airman First Class Michael Davis, a Headquarters SAC photo interpreter, determined to be SS-4 medium range ballistic missiles. The Soviets had placed missiles with nuclear warheads only 90 miles from our shores. Over the next six days, only the senior civilian and military leadership of the US was aware of the presence of these missiles - the Joint Chiefs recommended to President Kennedy that we prepare for an immediate invasion of Cuba to destroy the missiles. On Saturday morning, 20 October, I was in Job Control monitoring maintenance, as maintenance began preparing the second C-Site missile for the series of ten lox loadings. They had just removed the RP-1 and the ordnance, and were installing the television cameras so we could do the first test on Monday. The 9th Bomb Wing Command Post senior controller, a lieutenant colonel, called and , said “Lieutenant, SAC had directed that Charlie-2 be returned to alert immediately and all missiles are to stay on alert until further notice. They told us to ask no questions - just to do it now.” I called the Site Commander, LtCol Tom Pasco, and passed along the message. Our maintenance supervisor, Maj Ted Grossholz, asked me for more specific information - I told him he had better talk to the command post. He called me back a minute later and just said “We are returning the missile to alert.”

Over the next two days, there was a lot of anxiety around our missile squadron and the base. We knew something big was going on - but weren’t told a lot. B-47s and C-97s began departing, along with the EB-47 post attack command and control aircraft, and we began manning the sites with two crews. We found out the reason when President Kennedy addressed the nation on Monday evening, 22 October. There were missiles in Cuba - and we were ready to go to war. As the president spoke, the US military - and SAC - went to Defcon 3. Almost all our bombers and tankers left - we missileers were left alone and on alert. SAC increased the B-52 airborne alert force from 12 to 66 bombers, and 1,519 bombers were armed with nuclear weapons and dispersed around the world ready. Almost 200 new Atlas and Titan I missiles sat on full alert, needing only lox or lox and fuel for launch. Overseas, Mace, Thor and Jupiter missiles were also ready, and our BOMARC and airlaunched missileers were equally busy and on alert. Everything was manned 24 hours and day, and we continued keeping two combat crews at each site. On Wednesday, 24 October, the Joint Chiefs directed us to Defcon 2 - SAC was at its highest Defcon in history. General Tom Power, the CinCSAC, broadcast a personal message on the Primary Alerting System to all SAC wings, “This is General Power speaking. I am addressing you for the purpose of reemphasizing the seriousness of the situation the nation faces. We are in an advanced state of readiness to meet any emergencies, and I feel that we are well prepared. I expect each of you to maintain strict security and use calm judgement during this tense period. Our plans are well prepared and are being executed smoothly. If there are any questions concerning instructions which by the nature of the situation deviates from normal, use the telephone for clarification. Review your plans for further action to insure that there will be no mistakes or confusion. I expect you to cut out all nonessentials and put yourself in a maximum readiness condition. If you are not sure what you should do in any situation, and if time permits, get in touch with us here.” All of us now realized how serious the situation was - we were very close to nuclear war. We called it Defcon 2, but we were as close to Defcon 1 as we could be. For the liquid fueled systems, crews sat ready to start the lox loading sequence - they were fifteen minutes from launch. Our maintenance folks learned a lot of ways to keep missiles on alert. We shortened the time that work platforms were lowered for system checks, and there were “workarounds” probably not recognized by Martin - piano wire works wonders to ensure a valve that must open when the launcher starts up really opens. On Friday, October 26, the first Minuteman I missile at Malmstrom was placed on alert due to the hard work of wing and contractor personnel. Four more attained alert by 30 October. Saturday, 27 October, was called “Black Saturday” - an RB-47 crashed on takeoff from Bermuda, killing all four crewmembers, and Maj Rudolph Anderson’s U-2 was shot down by a Soviet SAM over Cuba. A giant invasion force was being formed in Florida - and war seemed unavoidable. The civilian and military leadership continued to work to resolve the crisis. Messages and letters went back and forth between Khrushchev and Kennedy, and options about the US missiles in Turkey and Italy were discussed. The Soviet leader agreed to remove the missiles from Cuba and we slowly returned to normal. SAC stayed at an increased alert until 20 November, when we finally returned to Defcon 4. Thanksgiving was only two days away, so we were kept busy and on base over the weekend - probably to keep us safe over a “long weekend” The crisis was over - and even Robert McNamara attributed our success to SAC - as he stated, “Kruschchev knew without any question whatsoever that he faced the full military power of the United States, including its nuclear weapons.” McNamara considered SAC’s nuclear might to be “the reason, and the only reason” Khrushchev withdrew his missiles. SAC’s calm, disciplined, methodical operation proved to be the key to the successful outcome of the crisis. All of us who were Missileers in that October forty years ago can be proud of our contributions at a critical time in our history. References: - Strategic Air Command, The Story of SAC and its People, Turner Publishing, Paducah, KY, 1995 - Development of Strategic Air Command, Office of the Historian, Headquarters, SAC, March 1976 - Cuban Missile Crisis: Timeline - The Cuban Missile Crisis, A Chronology of Events Genesis of the Missile Program «AAFM», December, 2002. Newsletter of «Association of Air Force Missileers»

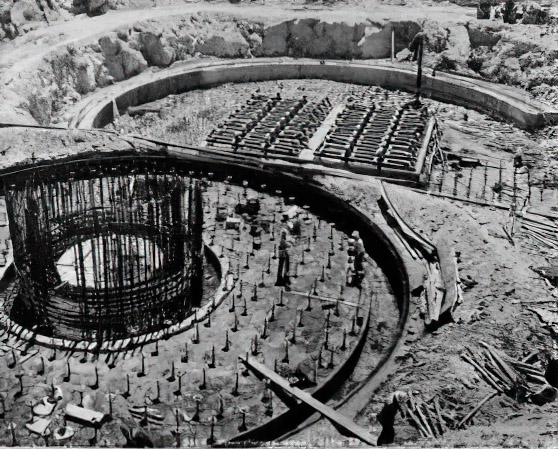

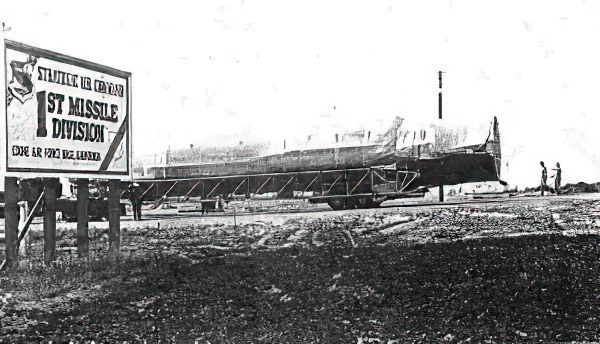

I was reassigned from Deputy Commander, 1805th AACS Wing at Pepperrell AFB, Newfoundland to Western Development Division in Los Angeles in the spring of 1957. WDD was developing the Atlas with contractual assistance from Thompson, Ramo, Woolridge (Dr. Simon Ramo as Chief Scientist) and Convair as Atlas contractor. WDD was commanded by BGen Bernard A. Schriever who had spent several years at the Pentagon developing the ballistic missile concept. One third of his hand picked staff had PhD’s and Masters degrees. There was an academic air prevailing at WDD. Staff meetings had a language of cryogenics, apogees, UDMH, gimbals. orbital mechanics, LOX, ablation, ad infinitum. My career had been primarily with “hot solder and wet cement” so I knew I had much to learn, but, events took a fortuitous turn. The 392ABG was being expanded and the 704th Strategic Missile Wing and 1st Missile Division would relocate to Cooke AFB. We were offered the opportunity to volunteer for reassignment there. I was well aware of the dangers of volunteering for anything when I was an enlisted man, however the Personnel Officer was persuasive with his description of Cooke as “a base north of Santa Barbara, on the ocean with sandy beaches, balmy breezes and a sunny clime’. Just think, a release from LA smog and congestion. Needless to say I was first in line. Within a week, with two trunks strapped on the roof, two children buried in the rear and my wife Tex beside me, we headed north to our new military home with a song in our hearts. We sailed through Santa Barbara but as it faded in our rear view mirror we found ourselves in wide-open country. When we turned west on the Lompoc Road our surroundings became more rustic. Late in the afternoon we entered Lompoc and as I gassed up I asked the attendant how to get to Cooke AFB. He said he never heard of it but there were some soldiers north of Lompoc and I might try there. I found the gate and entered the USDB, which was a Federal prison! I was told to continue north. The gravel road narrowed but I was undaunted in my search for Cooke AFB. As 1 topped a small rise I spotted a man near the road and called out “is this the road to Cooke?” He shouted back “no hable Inglais!” The army had leased Cooke out for grazing and he was one of many Mexican shepherds tending their flocks. I knew now that my “volunteerism” of the previous week was being fulfilled. With nightfall upon us I was elated to view a cantonment ahead, which was our destination, Cooke AFB. It was a large complex of two story WWII GI barracks, one story wooden administrative buildings, maintenance buildings and motor pools. Most were unoccupied but in a caretaker status. A Corps of Engineer LtCol was in charge of most of the base facilities. There were about 50 to 75 enlisted men and several AF officers. The Provost Marshal was a Major with several administrative and supply officers. This was the fledgling ballistic missile program of the USAF and I was proud to be a charter member!

I was appointed Director of Communications/ Electronics of the 1MD and immediately started setting up my office in a converted barracks. The telephone central consisted of an army cord and jack switchboard with a telephone operator in attendance. The telephone book was a 4x5 card with printed subscribers names and numbers. Some subscribers had field telephones. Most of our time was spent reviewing base construction plans, routine staff work for WDD and supervising the rehabilitation of base facilities. Things were soon to change with a resounding bang. On 4 October 1957 the USSR announced launch of Sputnik and it was circling the planet every ninety minutes! October 5th all hell broke loose. The Air Staff was anxious to learn about this totally new threat. What was it all about? Where were we? Could we do this? Etc. Needless to say the following months were filled with TDY visitors with their briefcases and golf clubs attending briefings and taking the word back to the Pentagon. On 3 November the USSR announced it had launched Sputnik II with a passenger, Laika the dog. Now the activity increased to a fever pitch. It became necessary to declare a moratorium and limit visits to “need to know”. The expedited construction programs with scores of civilian contractors created a serious problem in the cable system on the base. Excavation equipment would run willy-nilly on the base and cut 200 and 400 cable pairs several times a week. When I confronted the operators they would shrug it off with “Forget it, our insurance company will cover it”. I was told to solve this problem post haste! I came up with a simple solution. I notified all contractors future cable cuts were to be turned over to the FBI as suspected sabotage of the missile program. Cable cuts fell to zero. On 4 October 1958, Cooke was dedicated as Vandenberg AFB. I was Master of Ceremonies and developed a great program with bands, flags and dedicatory speeches with Mrs. Hoyt Vandenberg arriving on the parade grounds in a 1958 pink Cadillac with huge tailfins. The reviewing stand had over twentyfive stars, from one star to four stars. It was truly a banner day. Incidentally, it was one year to the day of the launch of Sputnik, I do not know if that was intended or not. The base population grew by thousands and the string of vehicles would extend for miles winding to and from the base. Missile complexes, administrative buildings, Capehart housing, commissary, BX buildings and warehouses, etc., created a round-the-clock activity. Many of the WWII barracks were moved and converted for a new role in the missile and space program. It was not unusual to see two buildings pass each other going in opposite directions! A case of separate contractors fulfilling their separate contracts. The first Officers Club was created by assembling six WWII barracks in a “U” shape, a far cry from the present building. The first missile launch was a Thor IRBM on 16 December 1958. The base declared a holiday so we could witness this historic event. The countdown took hours but a festive atmosphere prevailed and rounds of applause rose in a crescendo as it majestically lifted off and soared down range. This event was outdone on 28 February 1959 when a historic first polar orbiter satellite, Discoverer I, was launched successfully.

The Atlas complex with its huge girdered tower and MOD I guidance system was being completed. This weapon system relied on radar guidance, which was extremely vulnerable to possible jamming either intentional or unintentional. We were in the Cold War! The command destruct transmitter was on triple alert but a command destruct at this stage of the game would have been extremely damaging. But, it also expedited the R&D on inertial systems. We launched an Atlas on 9 September 1959 and as a result of that success we were ordered to place an Atlas with a nuclear warhead on alert in October. This was to let the world know the USAF had a real deterrent. The press seized the opportunity to photograph this gleaming giant missile spewing a vapor stream. It was awesome. I don’t know if Pravda published it ,but I feel sure they knew about it. On base we referred to it as our “Hollywood capability”. With the successful launches of the three ballistic missiles it now became necessary to survey for future silo locations. A task force of seven highly qualified officers from communications/electronics, logistics, personnel, transportation, public relations and operations were provided a list of about twenty possible locations that were to be identified as potential missile locations. Our orders were to be incognito, to use only first names in our meetings with the towns people and under no circumstance reveal the Air Force interest in the area. We traveled in rental vehicles and covered seven states. From Kansas to North Dakota in the north, and westerly to Washington. Upon entering a town we would go to city hall meet the mayor, and usually the sheriff and city staff and begin our survey. The inquiry usually centered around water and electrical power, railhead and interstate highway access, water tables and general geological data, and other demographics. Of course in the smaller towns rumors ran thick and fast that we were communists, foreign spies, or representatives of Fortune 500 companies seeking a new location for a huge factory. We left town quietly after a day or two and proceeded on our journey. The “tinkle and trickle towns (towns where the telephone and water lines identified the boundaries) were the most suspicious of our activities and often tailed us. This wasn’t true in larger towns such as Minot, Cheyenne or Spokane. Our team returned to VAFB. compiled our findings and forwarded them to WDD where the selection of the final sites was made. We finally felt we had accomplished our mission when we launched a solid propellant inertially guided intercontinental missile the Minuteman in 1962. It was a historic date for the free world and a long way from the date when I asked a Mexican sheepherder how to get to Cooke AFB.

|