|

|

|

|

|

Charlie Simpson

Atlas – The First ICBM

© «AAFM», March, 1999.

Our address: en@rvsn.info |

|

See also:

|

|

The Atlas was our first intercontinenal ballistic missile (ICBM) - the first missile to put an American astronaut into orbit around the earth - and still one of the workhorses in the United States space program. Atlas has its roots in the Convair MX-774, developed and tested in the late 1940s, during the United States Air Force’s early research into missiles. Atlas continues today in its latest configurations, and Lockheed Martin, the manufacturer of the current Atlas space launch vehicles, has decided to call its newest launch vehicle the Atlas V.

The MX-774 - In late 1945, the Army Air Force began defining four categories of missiles to be developed over the next ten years. The Consolidated Vultee Aircraft Corporation (Convair) proposed, and received funding to study a supersonic, ballistic, rocket-powered missile capable of delivering a 5,000 pound warhead over ranges up to 5,000 miles with an accuracy of 5,000 feet. Convair project manager Karl J. Bossart led the team that began work on this revolutionary new weapon system.

Atlas D Missiles at Warren |

While the design of the «MX-774» was, in some ways, a takeoff from the German V-2 ballistic missile, Bossart and his team made many significant improvements in missile design. The V-2 used double wall propellant tanks – the MX-774 used the external skin as the skin of the tanks. The entire V-2 reentered the atmosphere with its warhead – the MX-774 warhead separated from the missile after powered flight ended. The MX-774 used swiveling, or gimbaled engines, eliminating the need for steering vanes.

In 1947, after deciding that ballistic missiles wouldn’t provide any tangible results in the next eight to ten years, the Army Air Force decided that cruise missiles like Snark and Navaho held more promise for the future. Convair was allowed to continue testing of the three test vehicles under construction. Both of the first two tests failed because of engine failure, the first at one mile altitude and the second at ten miles. The third and final flight lasted for 51 seconds, but also exploded due to a liquid oxygen valve closing unexpectedly. The tests did prove the concepts of gimbaling engines, lightweight airframe construction, nose cone separation and the autopilot and command system.

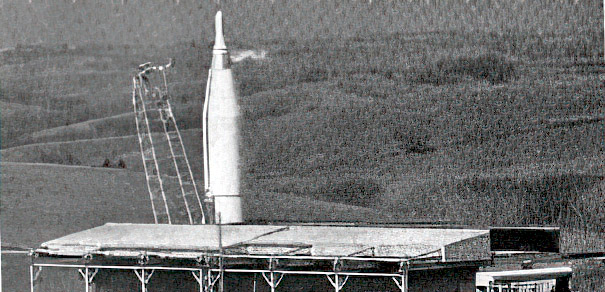

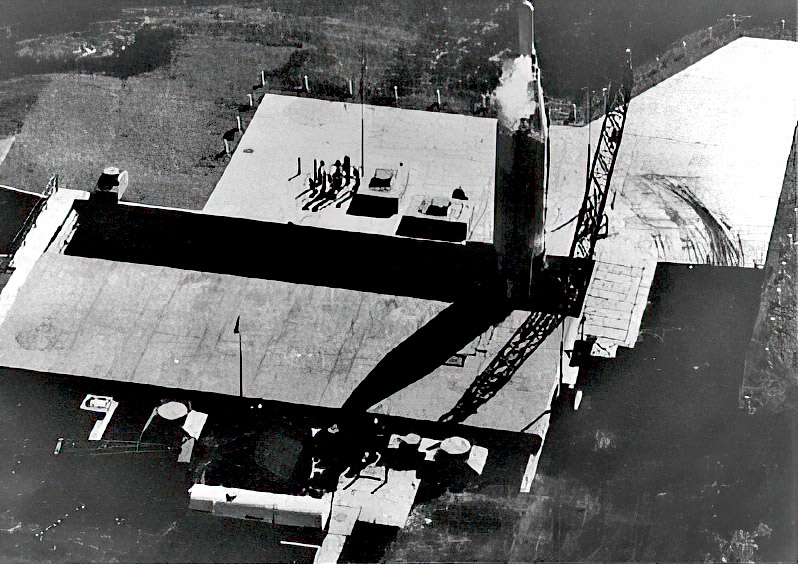

Atlas D Erected and Loaded |

«MX-1593», Project «Атлас» – After cancellation of the MX-774, the new United States Air Force funded a Convair study of a long-range missile capable of carrying an 8,000 pound warhead a distance of 5,000 miles, with an accuracy (circular error probable) of 1,500 feet. Convair took the Atlas name from its parent company, the Atlas Corporation. The ballistic missile concept would be a 160 foot long, 12 foot diameter missile using the North American alcohol – LOX 120,000 pound thrust engine developed for the Navaho combined with a Reaction Motors 20,000 pound thrust engine. The Atlas would have five or seven engines, would carry a 7,000 pound warhead and would have a CEP of 1 mile.

Over the next few years, until late 1954, several factors impacted the development of the Atlas and ballistic missiles in general. A roles and mission disagreement between the Army and Air Force went on for some time – the Army contending that missiles were “artillery” and should all be under the control of the Army. The size of nuclear weapons was decreasing as more weapons were tested, and advances in technology allowed changes in the concepts for design of ballistic missiles. Over this period, the configuration of Atlas was somewhat fluid – the size and weight, number of engines and warhead weight were all factors that varied as discussions and studies continued.

Finally, during 1954, plans for Air Force ballistic missiles firmed up. The Western Development Division, under Major General Bernard Schriever, was formed in Los Angeles to oversee ballistic missile development.

WS-107A, the SM-65 – In early 1955, the configuration for Atlas was finalized – a 240,000 pound vehicle with two 135,000 pound thrust North American rocket engines and a third sustainer engine of 60,000 pounds thrust. At the same time the “stage and a half” Atlas was approved, the two-stage Titan I was also approved for development. This two-track system provided a backup in case one concept failed, and was reflected in the development of guidance systems and other subsystems. Throughout the development of the two missiles, the basing configuration also remained fluid, with the total number of missiles, missile sites, radio guidance sites and missile units and bases reviewed and changed numerous times.

|

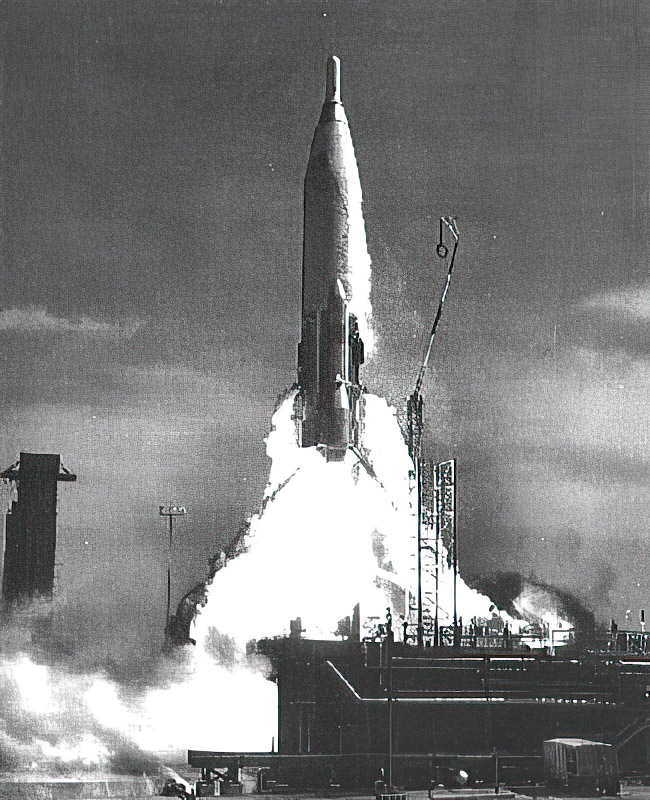

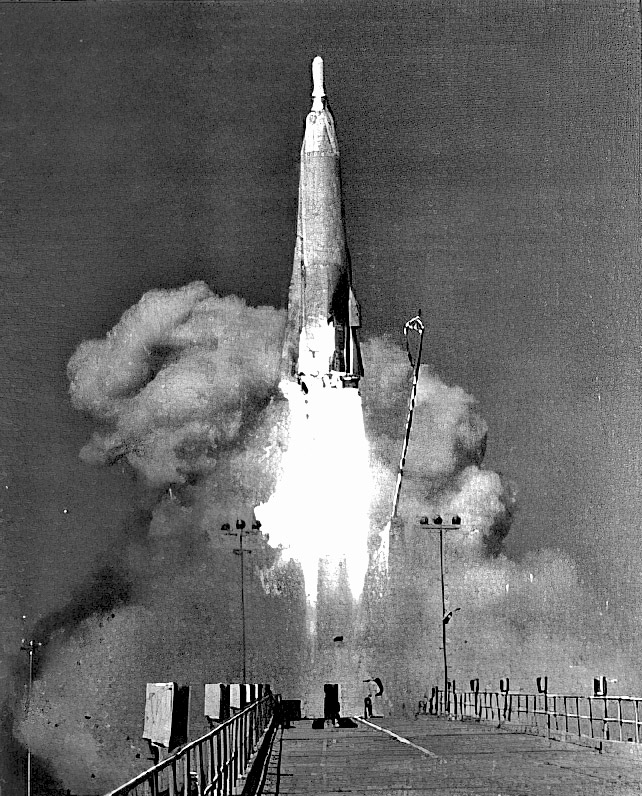

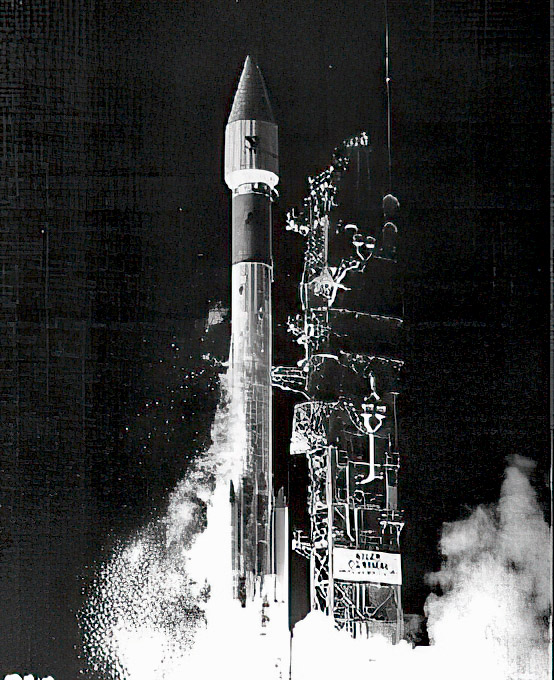

First Flights – the first test launch of an Atlas, an A model with only the two booster engines, took place at Patrick AFB, Florida on 11 June 1957. The engines failed shortly after launch and the missile was destroyed after less than a minute of flight. The second test, on 25 September, also failed for the same reason. On 17 December 1957, the third Atlas launched for two full minutes of powered flight and was declared a complete success.

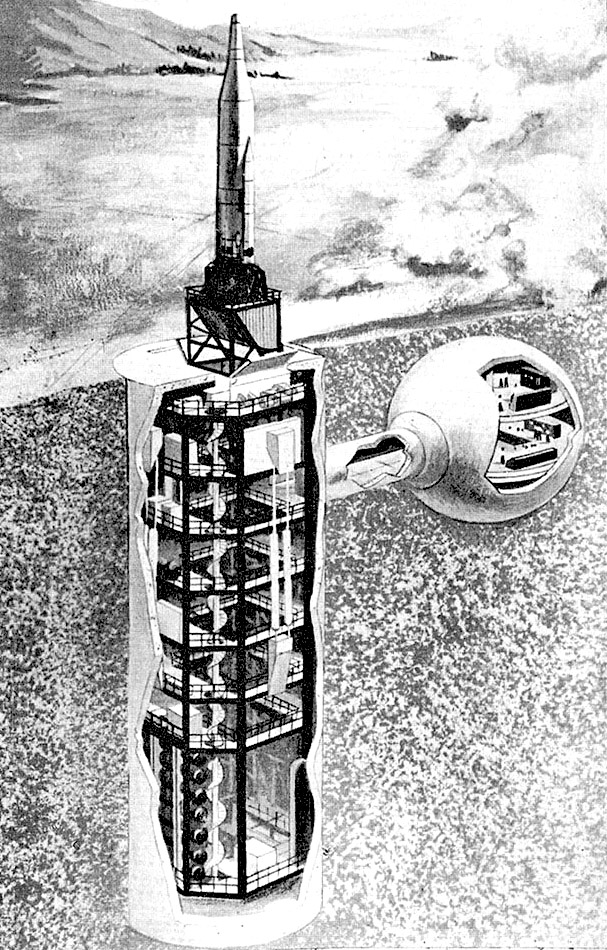

Atlas F Silo |

«Атлас D»

Atlas D – The 360,000 pound thrust SM-65D, later the PGM and CGM-16D, was deployed at Vandenberg AFB, California, in the 576th Strategic Missile Squadron (SMS), at Francis E. Warren AFB, Wyoming in the 564SMS and 565SMS and in the 566SMS (later the 549SMS) at Offutt AFB, Nebraska. The first Vandenberg missiles were deployed in soft complexes with gantries. The Warren and Offutt configuration included three above ground “coffins” at each site, with three missiles, a control center and a radio guidance system. A single missile crew controlled three missiles. The 564SMS had two sites, the other two squadrons had three each. At the Atlas D operational sites, the roof of the coffin was rolled back, the missile erected from horizontal to vertical, liquid oxygen and rocket propellant (RP-1) added and the missile was then ready for launch. Each site could launch one missile at time – the radio guidance system would guide one missile to completion of powered flight before the second was launched. The first Atlas missile was placed on alert at Vandenberg on 31 October 1959.

Atlas E – The SM-65E (CGM-16E) had improved engines for a total of 389,000 pounds of thrust, a larger warhead and all-inertial guidance. Each of the three Atlas E squadrons (567SMS at Fairchild AFB, Washington, 549SMS (later the 566SMS) at Warren and the 548SMS at Forbes AFB, Kansas) had nine missile sites. The 576SMS at Vandenberg had one Atlas E site. The E sites consisted of a “semi-hard” coffin with the roof at ground level. Like the Atlas D, the roof was retracted, the missile erected, propellants loaded and the missile was ready for launch. Since each site was independent, with all-inertial guidance, a separate launch crew manned each missile site.

Atlas F – The SM-65F (HGM-16F) had 390,000 pounds of thrust and all-inertial guidance. The Atlas F was deployed in a hardened silo with an adjacent control center, with one combat crew per missile. Each of the six Atlas F squadrons had twelve silos scattered around the support base. These were the 550SMS, Schilling AFB, Kansas, the 551SMS, Lincoln AFB, Nebraska, the 556SMS, Plattsburgh AFB, New York, the 577SMS, Altus AFB, Oklahoma, the 578SMS, Dyess AFB, Texas and the 579SMS, Walker AFB, New Mexico. The Atlas F sat vertically in the silo on a giant elevator platform. At the start of the launch sequence, the liquid oxygen was loaded onto the missile from the underground LOX storage tank, then the two large blast doors over the silo opened and the elevator raised the missile topside for launch.

Fairchild Atlas E |

Pressurization and Stretch – The airframe of the Atlas is unique – the missile is a thin stainless steel shell that depends on the presence the propellants to maintain its structure. One of the revolutionary developments of Bossart’s original MX-774 group, this design results in a lighter airframe, but requires constant attention to ensure that the missile doesn’t collapse. When the missile is empty of fuel and oxidizer, it must be in “stretch” or pressurized, whether it is in the silo or coffin or on the missile trailer used to transport it. If the stretch mechanism is disconnected without pressure in the missile, it collapses like a flat tube of toothpaste. A number of missiles were lost during the period that Atlas was operational as an ICBM.

Lox-Loading Exercises – throughout the operational life of the Atlas, simulated launch exercises were conducted to verify the launch capabilities of the missiles. Every missile was tested a number of times during its lifetime, and an intensive test of all Atlas ICBMs was conducted immediately after the Cuban Crisis. Early operational readiness inspections (ORIs) conducted by the Strategic Air Command indicated reliability problems with both Atlas and Titan I, and missile units regularly failed inspections in the early years. An ORI at an Atlas unit was a two-week period filled with intense activity. When the Inspector General team landed at the base, the unit was told to prepare its missiles for dual-propellant loadings. Base maintenance teams removed the warhead and replaced the explosive ordnance with simulators, and television cameras were placed around the coffin or silo. Each missile was exercised independently, with a simulated launch message initiating each countdown. The missile crew, with the IG team members looking over their shoulders, went through the entire launch countdown, with successful missiles completing a simulated flight to their targets. ORI standards dictated that about two thirds of the unit’s missiles must be successful for the unit to pass the ORI – few Atlas units were able to pass during the short life of the system. Several dual propellant loadings were spectacular failures – three at Walker and one at Altus. The failures resulted in explosions that destroyed the missile silos. Walker troops joked about the “early” phaseout of the 579SMS. Atlas was an exciting system for crewmembers and maintenance.

«Atlas Centaur» |

Atlas and Space - The brand new Atlas entered the space business early in its lifetime - in September, 1959, an Atlas D was the booster for the first Project Mercury test flight (Big Joe I), and on 20 February1962, an Atlas carried John Glenn to orbit around the earth. For forty years, Atlas has been the booster for satellites, space probes, moon and solar system missions and more, using a variety of upper stages, including the Agena and Centaur. Atlas missiles are still being manufactured by Lockheed Martin in Denver, and will continue to be a space workhorse well into the next century.

– Air Force Missileers, Turner Publishing Co., 1998

– Ballistic MisSiles in the United States Air Force, 1945-1960, Jacob Neufeld, Office of Air Force History, 1990

– From Snark To SRAM: A Pictorial History of Strategic Air Command Missiles, Office of the Historian, SAC, 1976

– To Defend and Deter, The Legacy of the US Cold War Missile Program, John C. Lonnquest and David F. Winkler, USACERCL, 1996.

– A History of USAF Ballistic Missiles, Ernest G. Shwiebert, Frederick A.Praeger, 1964

|